Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Trauma Inj > Volume 35(3); 2022 > Article

-

Case Report

Management of a traumatic anorectal full-thickness laceration: a case report -

Laura Fortuna, MD1

, Andrea Bottari, MD1

, Andrea Bottari, MD1 , Riccardo Somigli, MD2

, Riccardo Somigli, MD2 , Sandro Giannessi, MD2

, Sandro Giannessi, MD2

-

Journal of Trauma and Injury 2022;35(3):215-218.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20408/jti.2021.0049

Published online: May 19, 2022

- 2,389 Views

- 125 Download

1Department of General Surgery, AOU Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy

2Department of General Surgery, San Jacopo Hospital, Pistoia, Italy

- Correspondence to Laura Fortuna, MD Department of General Surgery, AOU Careggi University Hospital, Largo Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla, 3, Firenze 50134, Italy Tel: +39-335-651-3587 E-mail: laura9.fortuna@gmail.com

Copyright © 2022 The Korean Society of Traumatology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

- The rectum is the least frequently injured organ in trauma, with an incidence of about 1% to 3% in trauma cases involving civilians. Most rectal injuries are caused by gunshot wounds, blunt force trauma, and stab wounds. A 46-year-old male patient was crushed between two vehicles while he was working. He was hemodynamically unstable, and the Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma showed hemoperitoneum and hemoretroperitoneum; therefore, damage control surgery with pelvic packing was performed. A subsequent whole-body computed tomography scan showed a displaced pelvic bone and sacrum fracture. There was evidence of an anorectal full-thickness laceration and urethral laceration. In second-look surgery performed 48 hours later, the pelvis was stabilized with external fixators, and it was decided to proceed with loop sigmoid colostomy. A tractioned rectal probe with an internal balloon was positioned in order to approach the flaps of the rectal wall laceration. On postoperative day 13, a radiological examination with endoluminal contrast injected from the stoma after removal of the balloon was performed and showed no evidence of extraluminal leak. Rectosigmoidoscopy, rectal manometry, anal sphincter electromyography, and trans-stomic transit examinations showed normal findings, indicating that it was appropriate to proceed with the closure of the colostomy. The postoperative course was uneventful. The optimal management for extraperitoneal penetrating rectal injuries continues to evolve. Primary repair with fecal diversion is the mainstay of treatment, and a conservative approach to rectal lacerations with an internal balloon in a rectal probe could provide a possibility for healing with a lower risk of complications.

- The rectum is the least frequently injured organ in trauma, with an incidence of about 1% to 3% of trauma cases involving civilians, while 5.1% of rectal trauma cases result from war trauma. Of these, about 23% of cases are due to explosives. In civilians, most injuries are caused by gunshot wounds (approximately 70%–85%), while blunt force trauma (5%–10%) and stab wounds (3%–5%) account for the remaining cases [1]. Of these, extraperitoneal rectal injuries from blunt trauma are very rare in civilians and are usually accompanied by sacral or pelvic fractures associated with intraperitoneal injury [2]. In addition to being relatively rare given the protected position of the rectum within the pelvis, rectal injuries can be difficult to diagnose and are often overlooked [3].

- Intraperitoneal rectal lesions are managed in the same way as colonic lesions—that is, they are often treated with direct repair without diversion. In contrast, extraperitoneal rectal lesions are difficult to access and the transabdominal approach only allows the creation of a stoma for fecal diversion [4]. Extraperitoneal rectal lesions can be managed conservatively or surgically, depending on the extent of the lesion. There is currently no standardization of the management of minor injuries, but closure of the defect, when possible, seems to be beneficial [2]. In such cases, the optimization of access to extraperitoneal rectal lesions can allow effective primary repair and avoid the need for diversion. In this context, transanal minimally invasive surgery could increase the likelihood of successful primary repair of extraperitoneal rectal lesions [4]. Mortality rates have declined in recent decades, but despite advances in the management of trauma patients, mortality rates range from 3% to 10%, and the risk of further complications is 18% to 21%. Moreover, lesions of the rectum are rarely observed alone, given the close proximity to other organs and major pelvic vessels, damage to which can worsen the patient's outcome and make the management more complex. Considerable disagreement persists about the optimal management of such injuries [1,3].

INTRODUCTION

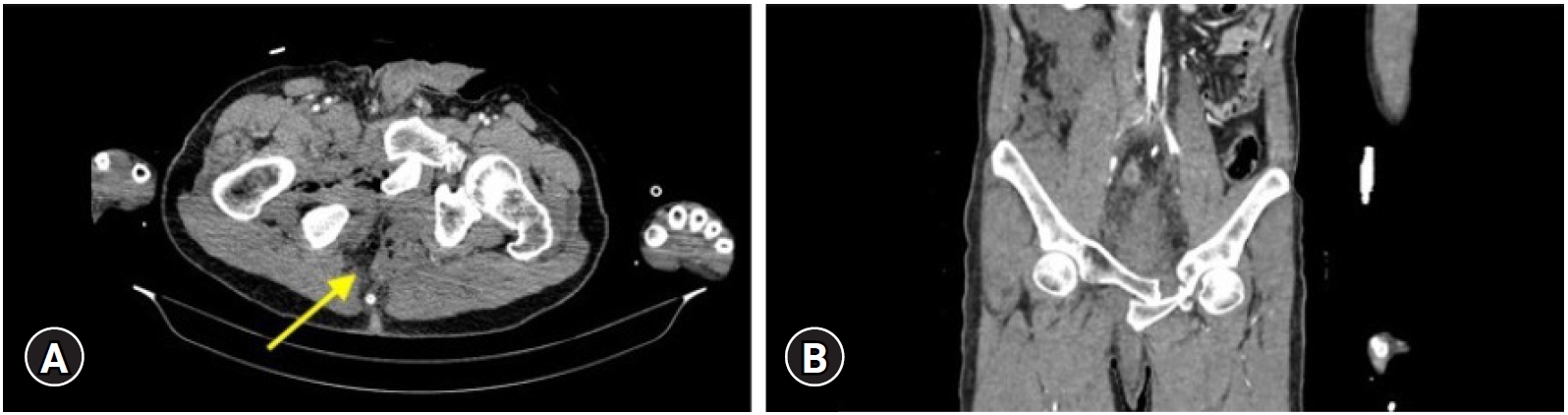

- A 46-year-old male patient was crushed between two vehicles at work. He arrived in the emergency room in a hemodynamically unstable condition, so he underwent damage control surgery with pelvic packing. Subsequently, a whole-body computed tomography scanperformed after hemodynamic stabilization showed a displaced fracture of the right hemi-basin, which was superomedially displaced with partial overlapping of the ilium with the pubic ischium and the branches of the symphysis (Fig. 1). Furthermore, fractures of both alae of the sacrum with diastasis of the stumps to the right and involvement of the foramina were noticed, with detachment and ascent of the cranial portion associated with fracture of the left iliac wing in the posterior aspect. There was also evidence of inhomogeneity of the periprostatic and membranous urethra, indicative of traumatic lesions. A rectal examination identified an extensive 270° extraperitoneal laceration on the anterior rectal wall. We performed second-look surgery 48 hours after the first operation, during which we stabilized the pelvic bone fracture with external fixators and performed cystostomy and loop sigmoidostomy. We decided not to proceed with primary closure of the rectal laceration given the high risk of stenosis that would have been posed by primary-intention healing with an extensive wound defect close to the anal sphincter. We then placed a Foley balloon in traction proximal to the tear to promote secondary intention healing for two purposes: to facilitate approximation between the proximal and distal flaps of the tear and to allow effective washing of the wound. After positioning the probe, several rectal washouts were carried out until satisfactory progress in rectal cleaning was observed. A methylene blue test was performed and showed no abdominal dye shedding. The postoperative course was uneventful. On postoperative day (POD) 13, a radiological examination with endoluminal contrast injected from the stoma after removal of the balloon showed no evidence of extraluminal leak. Rectosigmoidoscopy, rectal manometry, anal sphincter electromyography, and trans-stomic transit control showed normal findings, indicating that it was appropriate to proceed with the subsequent closure of the colostomy, which was performed 1 year later. The postoperative course was uneventful; the patient was regularly canalized on POD 3, showing good continence. The patient was then discharged on POD 5.

- Written informed consent for publication of the research details and clinical images was obtained from the patient.

CASE REPORT

- Guidelines for rectal injuries continue to evolve, and an emphasis is now placed on more conservative approaches [5]. Historically, the first studies were conducted on rectal trauma that occurred during wars. During World War I, direct repair of rectal injuries associated with the occasional use of diversion reduced mortality from about 90% to 67%, while in World War II, the use of deviation in addition to presacral drainage brought mortality to 30%. Finally, during the Vietnam War, with the progress of anesthetic techniques and the spread of antibiotic prophylaxis, direct repair associated with distal rectal lavage further reduced the mortality rate to 15% [3]. The preliminary evaluation of trauma patients must follow the principles of advanced trauma life support; anorectal lesions are evaluated secondarily, with digital rectal exploration, which has poor sensitivity for the identification of rectal lesions. Traumatic injuries of the rectum are classified in terms of their location (intraperitoneal vs. extraperitoneal) and according to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma rectum injury scale in grades from I to V [6]. However, the choice of treatment depends mainly on other factors such as hemodynamic instability, level of contamination, and other concomitant injuries [5]. As described in the literature, intraperitoneal rectal lesions are often treated with proximal diversion, although these patients showed a higher rate of abdominal complications (22% vs. 10%). However, extraperitoneal lesions can be much more challenging due to their deep location in the pelvis and their close relationships with surrounding structures. Extraperitoneal rectal lesions could be approached either transabdominally or transanally for proximal or distal injuries, respectively [7]. Patients with extraperitoneal lesions received proximal deviation in approximately 76% of cases, in 75% of which this was the only treatment. In the remaining cases, approximately 20% of patients underwent presacral drainage with or without distal rectal washout; both of these treatments have been associated with a 3-fold higher risk of abdominal complications. However, most of the lesions involved the extraperitoneal rectum, and 75% of these lesions were classified as grades I and II, with a high incidence of associated pelvic and abdominal lesions [8]. The causes for morbidity and mortality due to traumatic injuries of the extraperitoneal rectum include the difficulty in obtaining adequate exposure of the intervention field and the delay in diagnosis [5]. While surgeons initially shared the “4 D’s” strategy, given the good results since the Vietnam War, when it was proposed as the standard of care, the literature has subsequently begun to review the role of some of the “4D’s.” In particular, debates have focused on the need for repair, presacral drainage, distal rectal washout, and up to proximal diversion for extraperitoneal lesions [8,9]. Currently, guidelines recommend proximal diversion, without routinely proceeding with presacral drainage and distal rectal washout. Steele et al. [10] in 2011 found that there is no evidence for or against any treatment. Each treatment should be tailored for the individual patient. Chow et al. [11] stated that the literature supports stoma closure at any time between hospitalization and up to more than 3 months post-trauma. However, further studies are needed to establish a consensus on the timing of colostomy closure, given the high rate of associated complications (5% to 25%). The correct timing should be individualized based on individual factors, including nutritional status and clinical course [11]. Gash et al. [3] found that direct repair of the isolated lesion alone without diversion was comparable in terms of complications and mortality to suture repair of intraperitoneal lesions. Furthermore, patients treated with diversion associated with direct repair showed significantly longer hospital stays and a higher rate of postoperative complications than those who received direct repair without ostomy. Therefore, direct repair not associated with ostomy diversion may represent a viable strategy for the surgical management of isolated extraperitoneal lesions [3]. However, Brown et al. [8] suggested that extensive mobilization of the rectum should not be performed just to repair a rectal injury. Some authors observed, in appropriately selected patients, that secondary intention healing of extraperitoneal traumatic lesions of the rectum was possible. The conservative management of this type of full-thickness lesion has already been described in the literature after resection of rectal cancer and iatrogenic retroflexion rectal lesions during colonoscopy [12–14]. Associated urological injuries are common, with an incidence of approximately 25% in some studies, and although they are more frequent when the trauma is due to penetrating wounds, while approximately 40% of these injuries occurred following blunt trauma. Therefore, this type of accompanying injury should be suspected in patients with urinary symptoms or an abdominal fluid collection associated with poor urine output; in such cases, it is necessary to perform further diagnostic tests such as computed tomography with contrast or cysto-urethrography. According to some authors, patients with associated urological and rectal lesions more frequently underwent fecal deviation than those without urological lesions, with equivalent outcomes [3,15].

- The optimal management for extraperitoneal penetrating rectal injuries continues to evolve. We now know that every injury is unique, but previously all of these cases were treated with a “one size fits all” approach. In patients with a higher risk of complications who cannot achieve early abdominal closure, fecal diversion should be considered after damage control laparotomy. Primary repair with fecal diversion is the mainstay of treatment for extraperitoneal injuries; moreover, a conservative approach to rectal lacerations with an internal balloon in a rectal probe could provide a possibility for healing with a lower risk of complications.

DISCUSSION

-

Ethical statements

Written informed consent for publication of the research details and clinical images was obtained from the patient.

-

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

None.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: LF, AB, RS; Data curation: LF, AB; Formal analysis: LF; Methodology: RS; Project administration: RS, SG; Supervision: RS, SG; Validation: RS, SG; Writing–original draft: LF, AB; Writing–review & editing: all authors.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

- 1. Podda M, Sylla P, Baiocchi G, et al. Multidisciplinary management of elderly patients with rectal cancer: recommendations from the SICG (Italian Society of Geriatric Surgery), SIFIPAC (Italian Society of Surgical Pathophysiology), SICE (Italian Society of Endoscopic Surgery and new technologies), and the WSES (World Society of Emergency Surgery) International Consensus Project. World J Emerg Surg 2021;16:35. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 2. Hahn KY, Ko SY, Lee WS, Kim YH. Extraperitoneal rectal laceration secondary to blunt trauma: successful transanal endoscopic repair with hemoclips. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130:2384–5. PubMedPMC

- 3. Gash KJ, Suradkar K, Kiran RP. Rectal trauma injuries: outcomes from the U.S. National Trauma Data Bank. Tech Coloproctol 2018;22:847–55. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 4. Melland-Smith M, Chesney TR, Ashamalla S, Brenneman F. Minimally invasive approach to low-velocity penetrating extraperitoneal rectal trauma. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2020;5:e000396. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Guraieb-Trueba M, Sanchez-Robles JC, Perez-Morales OE, Garcia-Nunez LM. A novel approach for rectal trauma. The use of a transanal platform to repair a combined high-velocity rectal gun fire wound. J Coloproctol 2020;40:265–8.

- 6. Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, et al. Organ injury scaling. Surg Clin North Am 1995;75:293–303. ArticlePubMed

- 7. Trust MD, Brown CV. Penetrating injuries to the colon and rectum. Curr Trauma Rep 2015;1:113–118. ArticlePDF

- 8. Brown CV, Teixeira PG, Furay E, et al. Contemporary management of rectal injuries at Level I trauma centers: the results of an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma multi-institutional study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2018;84:225–33. ArticlePubMed

- 9. Levine JH, Longo WE, Pruitt C, Mazuski JE, Shapiro MJ, Durham RM. Management of selected rectal injuries by primary repair. Am J Surg 1996;172:575–8. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Steele SR, Maykel JA, Johnson EK. Traumatic injury of the colon and rectum: the evidence vs dogma. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:1184–201. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Chow A, Tilney HS, Paraskeva P, Jeyarajah S, Zacharakis E, Purkayastha S. The morbidity surrounding reversal of defunctioning ileostomies: a systematic review of 48 studies including 6,107 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis 2009;24:711–23. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 12. Karadimos D, Aldridge O, Menon T. Conservative management of a traumatic non-destructive grade II extraperitoneal rectal injury following motor vehicle collision. Trauma Case Rep 2019;23:100224. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Di Flumeri G, Carcaboulias C, Dall'Olio C, Moriggia M, Poiatti R. Anorectal and perineal injury due to a personal watercraft accident: case report and review of the literature. Chir Ital 2009;61:131–4. PubMed

- 14. Katano K, Furutani Y, Hiranuma C, Hattori M, Doden K, Hashidume Y. Anorectal injury related to a personal watercraft: a case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep 2020;6:226. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 15. Roche B, Michel JM, Deleaval J, Peter R, Marti MC. Traumatic lesions of the anorectum. Swiss Surg 1998;(5):249–52. PubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Figure

- Related articles

-

- Management of a traumatic avulsion fracture of the occipital condyle in polytrauma patient in Korea: a case report

- Delayed diagnosis of popliteal artery injury after traumatic knee dislocation in Korea: a case report

- Dual repair of traumatic flank hernia using laparoscopic and open approaches: a case report

KST

KST

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite