New horizons of Flaubert: from a barber-surgeon to a modern trauma surgeon

Article information

Ambroise Paré (1510–1590), a French barber-surgeon, is considered to have been a pioneer in the treatment of battlefield traumatic wounds. He reintroduced ligature of arteries, which had been introduced by Celsus and Galen, instead of cauterization during amputation [1].

However, medieval trauma surgeons, including Paré, did not have the legal right to treat diseases, which was the territory of physicians. Barber-surgeons were legally permitted to treat wounds, fractures, syphilis, cataracts, and gangrene. They pulled teeth and shaved, washed, and cut hair. However, the domain of diseases belonged to physicians. The ancestors of today’s medical practitioners are not university-trained, Latin-speaking medieval pedants, but humble, apprentice-trained barber-surgeons, craftsmen, and members of guilds, who provided most of the medical personnel for hospitals and armies until the 19th century [2].

The widespread introduction of firearms during the 16th century radically altered the landscape of conventional warfare in Europe. Extensive soft tissue damage, contamination from embedded projectiles, and the need for limb amputations increased dramatically. In the 16th century, the barber’s office, as a craft guild system, controlled the training of barbers and the establishment of barber shops. In the 17th century, the craft organization provided surgeons for the Army and the Navy [3].

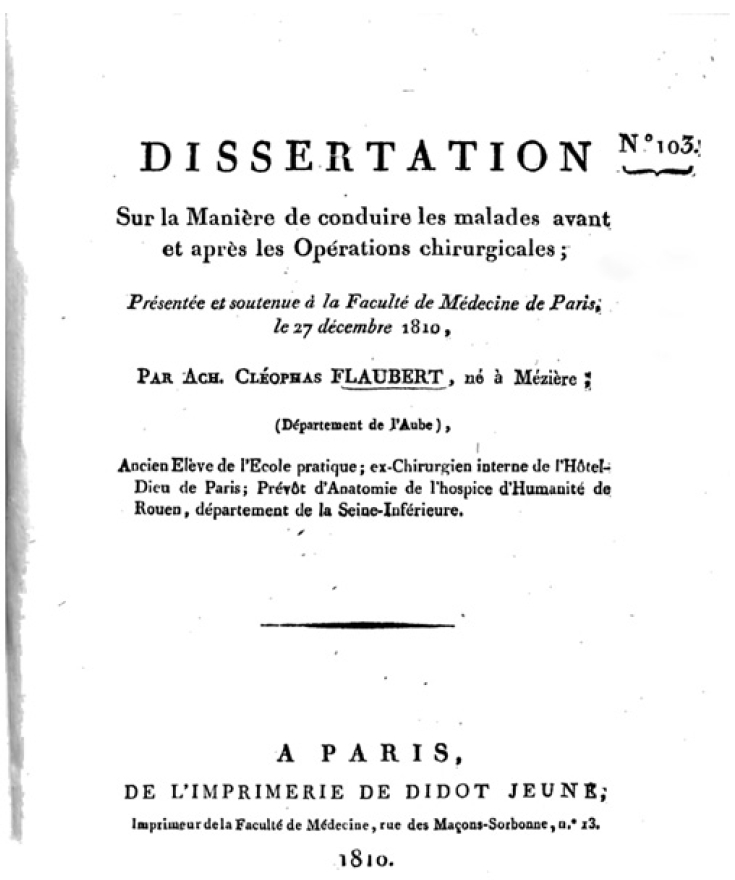

In 1810, a French surgeon named Achille Cléophas Flaubert, better known as father of the writer Gustave Flaubert, submitted a historical dissertation (Fig. 1) [4]. We can see his confidence in the competition between surgeons (chirurgiens) and physicians (médecins). According to his work, surgeons are at a superior or at least similar level to physicians.

One becomes a true surgeon—who shows his excellence when carrying out the maneuvers necessary to perform an operation that requires precise knowledge of anatomy, dexterity of the hand, finesse with almost every sense, and strength of spirit—only by drawing upon his precious expertise, unifying the skills and knowledge of a physiologist with those of a doctor, to consider the general temperament of the patient, the specific temperament of his or her organs, and the influence of any factor that could be related to the patient’s illness, and to seek out and apply—both before and after the operation—every possible way of achieving a successful outcome. Only then does one deserve the name of a surgeon or an operating physician; such a person unifies two sciences, medicine and surgery, that naturally go hand in hand with each other and weaken and falter as soon as they are separated. If anyone is still a partisan of the viewpoint that these two great branches of healing should be separated, let them look at the responsibilities of a surgeon and judge accordingly. The surgeon’s role encompasses the periods before, during, and after the operation—in the first stage, he must be a physician; in the second stage, a surgeon; and in the third, he becomes a surgeon again. (Translated by Andrew Dombrowski, PhD).

As a trauma surgeon, I absolutely agree with the preface of Flaubert’s dissertation. A good surgeon should be a good physician with some extra skills. Specifically, a good surgeon needs to learn how to operate, when to operate, and when not to operate. In addition to thorough knowledge and practical skills, a good surgeon is also expected to have common sense, which enables him or her to make sound practical judgments. In my opinion, a good trauma surgeon must first be a good surgeon, and a good surgeon must first be a good physician [5].

Notes

Ethical statements

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

Kun Hwang serves on the Editorial Board of Journal of Trauma and Injury, but was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (No. NRF-2020R1I1A2054761).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Andrew Dombrowski, PhD (Compecs Inc., Seoul, Korea) for his French translation.