Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Trauma Inj > Volume 36(2); 2023 > Article

-

Original Article

Quality monitoring of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta using cumulative sum analysis in Korea: a case series -

Hyunsik Choi, MD1

, Joongsuck Kim, MD2

, Joongsuck Kim, MD2 , Kwanghee Yeo, MD2

, Kwanghee Yeo, MD2 , Ohsang Kwon, MD2

, Ohsang Kwon, MD2 , Kyounghwan Kim, MD2

, Kyounghwan Kim, MD2 , Wu Seong Kang, MD2

, Wu Seong Kang, MD2

-

Journal of Trauma and Injury 2023;36(2):78-86.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20408/jti.2022.0069

Published online: December 21, 2022

- 2,121 Views

- 46 Download

- 2 Crossref

1Department of Emergency Medicine, Jeju Regional Trauma Center, Cheju Halla General Hospital, Jeju, Korea

2Department of Trauma Surgery, Jeju Regional Trauma Center, Cheju Halla General Hospital, Jeju, Korea

- Correspondence to Wu Seong Kang, MD Department of Trauma Surgery, Jeju Regional Trauma Center, Cheju Halla General Hospital, 65 Doryeong-ro, Jeju 63127, Korea Tel: +82-64-740-5024 Email: wuseongkang@naver.com

Copyright © 2023 The Korean Society of Traumatology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

Purpose

- Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is a state-of-the-art lifesaving procedure. However, due to its high mortality and morbidity, including ischemia and reperfusion injury, well-trained medical staff and effective systems are needed. This study was conducted to investigate the learning curve for REBOA in Korea.

-

Methods

- To monitor this learning curve, we used cumulative sum (CUSUM) analysis and graphs of mortality and aortic occlusion time within 60, 90, and 120 minutes for consecutive patients. The procedures performed between July 2017 and June 2021 were divided into pre-trauma center (pre-TC; July 2017–February 2020) and TC (February 2020–June 2021) periods.

-

Results

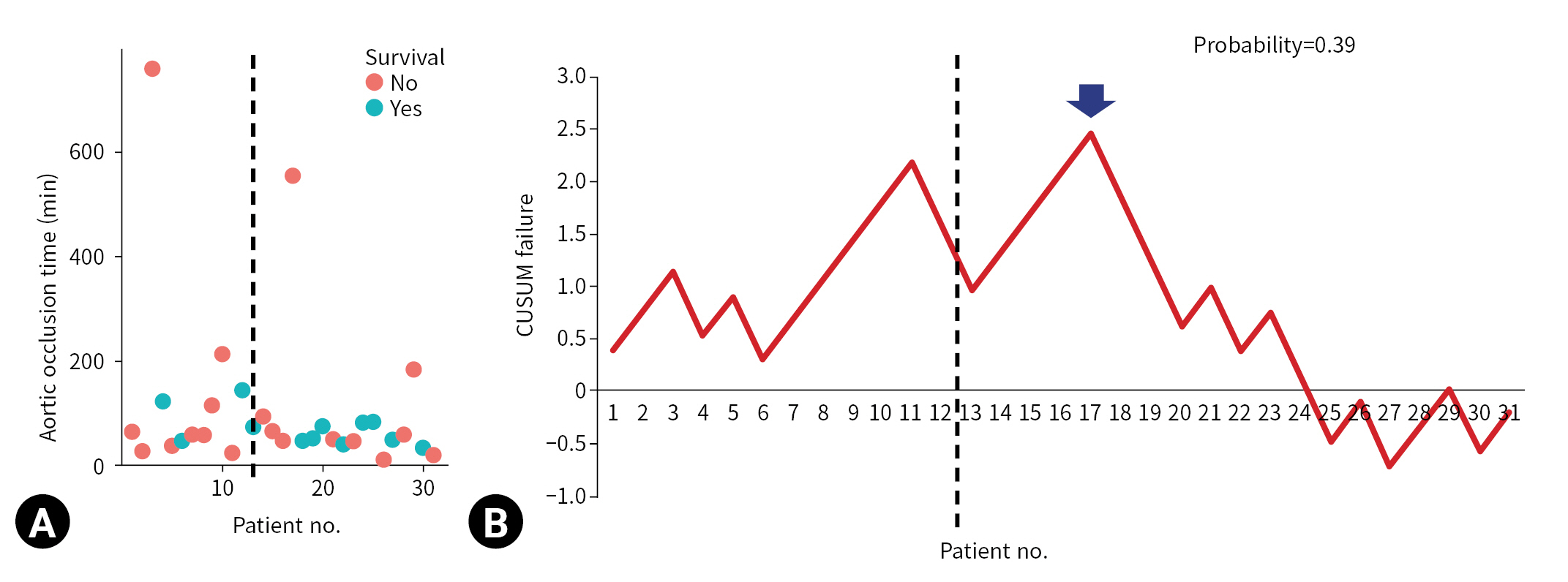

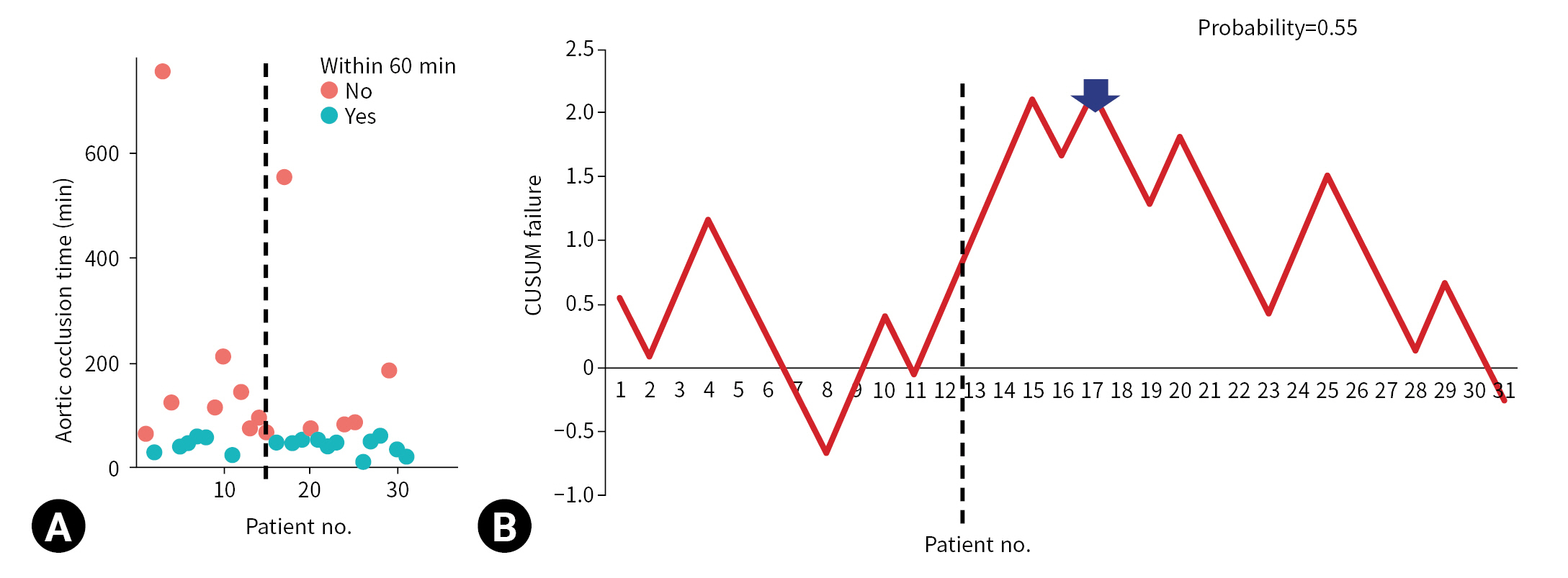

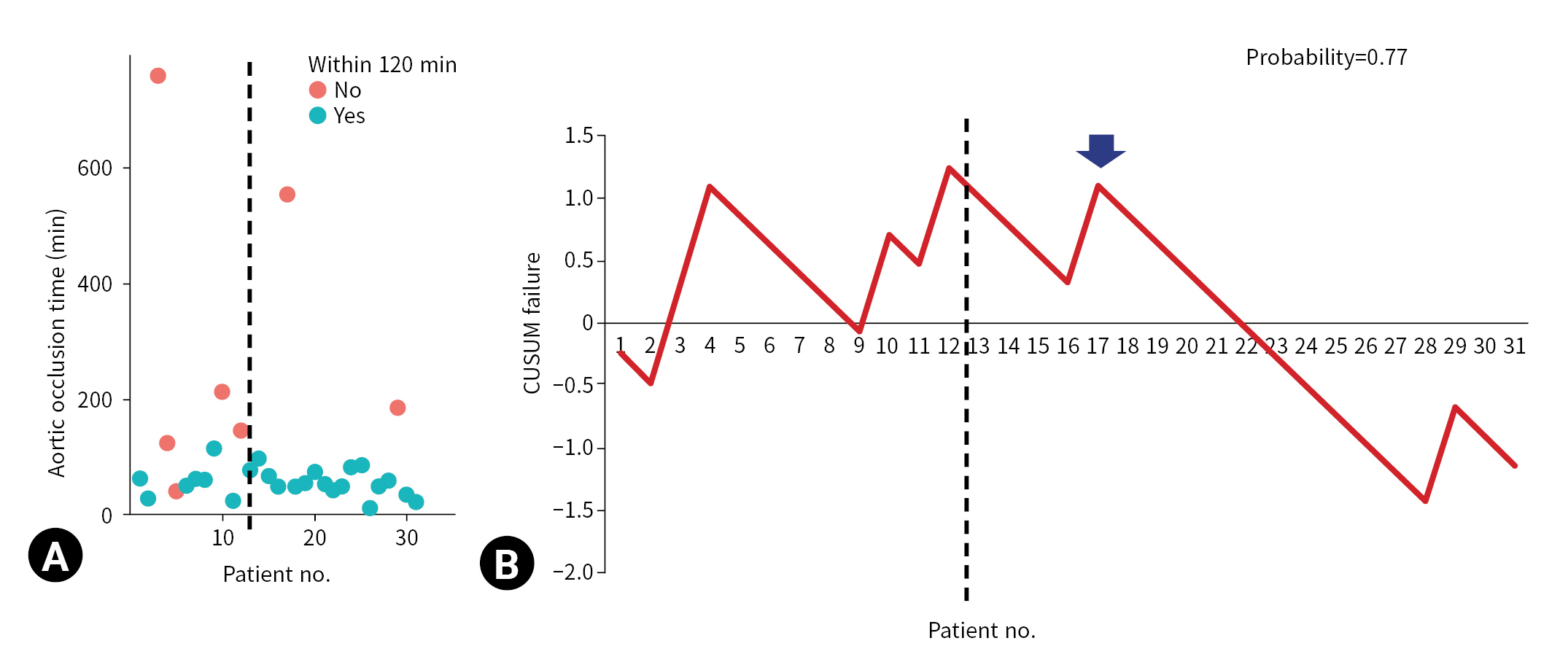

- REBOA was performed for 31 consecutive patients with trauma. The pre-TC (n=12) and TC (n=19) periods did not differ significantly with regard to Injury Severity Score, age, injury mechanism, initial systolic blood pressure, prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), or CPR in the emergency department. At the 17th consecutive patient during the TC period, CUSUM failure graphs for mortality and aortic occlusion time exhibited a downward inflection, indicating an improvement in performance.

-

Conclusions

- The mortality and aortic occlusion time of REBOA improved, and these parameters can be monitored using CUSUM analysis at the hospital level.

- Severe hemorrhage due to torso injury is a leading cause of death [1,2]. To reduce mortality from severe torso hemorrhage, damage control surgery and resuscitation have been introduced [1]. The core concept of damage control is prompt hemostasis, such as via emergency surgery or interventional radiology [1]. However, some patients are vulnerable to severe bleeding before effective hemostasis can be achieved and die before surgery or interventional radiology is performed. To rescue such patients, resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) was introduced for the temporary cessation or limitation of aortic blood flow [3]. REBOA is used as a bridge until definitive hemorrhagic control is achieved [4]. Resuscitative thoracotomy is substantially invasive and has high morbidity [5]; thus, REBOA has received considerable attention [6]. Moreover, the introduction of a 7F or 8F sheath minimizes iatrogenic limb ischemia.

- Well-trained staff and well-organized medical resources are required for an effective REBOA procedure. Medical staff should demonstrate proficiency in hemorrhage detection, diagnosis, vascular approach, identification of balloon position, and subsequent prompt hemostatic procedures such as damage control surgery and interventional radiology. Facilities and equipment such as trauma bays, interventional radiology rooms, operating rooms, point-of-care ultrasonography, and portable X-ray equipment should be well-organized. However, training and experience with medical resources are time-consuming. Moreover, experience with REBOA is insufficient in most trauma centers because the procedure is usually performed only in rare situations, such as in patients in severe shock [6,7]. Recently, centers with high REBOA utilization were found to be associated with lower mortality than low-utilization centers [8]. This implies that the learning curve at the hospital level is crucial. However, the learning curve associated with REBOA has not been examined in previous studies. Recently, the learning curve for damage control laparotomy in a Korean regional trauma center was evaluated using cumulative sum (CUSUM) analysis, which is a useful method for monitoring the performance of procedures [9–11]. Here, we investigated the improvement in the quality of the REBOA procedure and associated mortality using CUSUM at the hospital level.

INTRODUCTION

- Ethics statements

- This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cheju Halla General Hospital (No. 2022-L03-01). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

- Study design

- We reviewed the Korean Trauma Database for records from our trauma center from July 2017 to June 2021 to identify patients with trauma who underwent REBOA. Patients who died before REBOA, who did not undergo balloon inflation, or who underwent balloon insertion into the inferior vena cava due to a retrohepatic inferior vena cava injury were excluded from the study. Patient demographic and clinical data including mechanism of injury, age, sex, laboratory findings, vital signs, Injury Severity Score, Abbreviated Injury Scale score, postoperative outcomes, and REBOA-related time parameters were collected and analyzed.

- At our trauma center, two dedicated trauma bays, two operating rooms, and one interventional radiology room near the trauma bay were equipped for use by dedicated trauma staff. We divided our study into pre-trauma center (pre-TC; July 2017–February 2020) and TC (February 2020–June 2021) periods. Before February 2020 (the pre-TC period), trauma procedures were performed in the emergency department (ED), where nontrauma patients were also managed. From February 2020 onward (the TC period), all trauma procedures and patients were managed by attending trauma surgeons in a trauma bay. In the pre-TC period, the ultrasonographic image quality was poor due to aging equipment. Surgical instruments for laparotomy or thoracotomy were not prepared in the ED, and surgeons had to bring them from the operating room. In addition, the nursing staff members were not proficient in preparing REBOA kits, and most of them did not even know what REBOA was. The angiography room was located on a different floor from the ED, so patients had to be transferred by elevator. In contrast, in the TC period, point-of-care ultrasonography, a REBOA kit, portable X-ray equipment, surgical equipment for ED laparotomy and ED thoracotomy, and a trauma angiography room next door to the trauma bay were available after the establishment of dedicated trauma facilities. The dedicated nursing staff members were educated regarding the REBOA kit and surgical instruments and became more proficient at preparing them. In the pre-TC period, only three to five dedicated trauma surgeons worked at the trauma center. During the TC period, six to ten trauma surgeons and four emergency medicine faculty members were assigned to the trauma center.

- The indications for REBOA were patients with unstable vital signs (systolic blood pressure [SBP] <90 mmHg) and patients with severe intra-abdominal or pelvic hemorrhage. Femoral arterial puncture for REBOA was performed by a trauma surgeon using point-of-care ultrasonography or a blind method. The surgeon inflated the REBOA balloon by infusing 5 to 20 mL of saline. The balloon position was identified using portable X-ray equipment. When prompt hemostasis was required, ED laparotomy was performed appropriately. For patients with impending cardiac arrest before or after the REBOA procedure, ED thoracotomy was performed. After the return of spontaneous circulation, the aortic clamp used during the thoracotomy was converted to a REBOA setup. A hemostatic procedure was defined as the control of bleeding by laparotomy or angioembolization. The total REBOA occlusion time was measured from the time of initial balloon inflation to that of full deflation. A procedure was considered successful if the REBOA occlusion time was within 60, 90, or 120 minutes; this is because prolonged REBOA occlusion time can induce ischemic injury, which is associated with bowel ischemia, acute kidney injury, and limb ischemia. The primary outcome of our study was mortality, and the secondary outcome was aortic occlusion time. We hypothesized that aortic occlusion time is a surrogate marker of success in REBOA procedures.

- Statistical analysis

- Continuous data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges, and data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical data are presented as proportions. Proportions were compared using the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp) and R ver. 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

- CUSUM analysis

- The CUSUM procedure is a graphical method that is widely used for quality monitoring [9–11]. In this study, the CUSUM was calculated as follows: Sn = (Xi–p0i), where Sn is summation of the score, Xi=0 for success (for example, patient survival) and Xi=1 for failure (for example, patient death), and p0i denotes the predicted probability of failure of the procedure. The graph starts at 0 and is plotted from left to right on a horizontal axis. The curve moves up by 1–p0i for every case of failure (penalty) and down by p0i for every case of success (reward) on the cumulative failure graph. The improvement or deterioration of surgical outcomes can be identified intuitively based on the inflection of the CUSUM curve.

METHODS

- This is a case series. From July 2017 to June 2021, the REBOA procedure was performed for 31 trauma patients who were admitted to our hospital. A total of five trauma surgeons performed REBOA, with 20 procedures performed by one surgeon, eight procedures by another surgeon, and one procedure each by the remaining three surgeons. The baseline characteristics and a comparison between the pre-TC and TC periods are summarized in Table 1. Twelve (38.7%) and 19 patients (61.3%) were admitted during the pre-TC and TC periods, respectively. Twenty-nine patients (93.55%) experienced blunt trauma. The initial SBP levels of 13 patients (41.9%) could not be determined. Seven patients (22.6%) underwent prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Nine (29.0%) and eight patients (25.8%) underwent thoracotomy and laparotomy, respectively, in the ED. The median time from admission to REBOA was 31.0 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 18.0–67.0 minutes). The median total REBOA occlusion time was 60.0 minutes (IQR, 47.5–90.5 minutes). In 30 patients (96.8%), the balloon used during REBOA was placed in zone 1 (above the celiac axis), while it was placed in zone 3 (between the inferior mesenteric artery and the iliac bifurcation) in one patient (3.2%). Twelve patients (38.7%) survived the REBOA procedure. No significant differences were present in age, sex, SBP, Injury Severity Score, or Abbreviated Injury Scale score between the pre-TC and TC periods. The median REBOA occlusion time was shorter in the TC than in the pre-TC period, although the difference was not statistically significant (62.5 minutes [IQR, 44.0–134.5 minutes] in the pre-TC period vs. 53.0 minutes [IQR, 47.5–78.5 minutes] in the TC period, P=0.465). The survival rate was higher in the TC than in the pre-TC period, although the difference was also not significant (three patients [25.0%] in the pre-TC period vs. nine patients [47.4%] in the TC period, P=0.386). Table 2 shows a summarized comparison between nonsurvivors and survivors. The initial SBP was significantly lower in the nonsurvivor group. Nonsurvivors were significantly more likely to have undergone CPR at ED, ED thoracotomy, and ED laparotomy. However, no patient in the survivor group underwent CPR at ED, ED thoracotomy, or ED laparotomy.

- The CUSUM failure graph for survival is shown in Fig. 1. The CUSUM failure graphs for aortic occlusion time within 60 minutes, 90 minutes, and 120 minutes are shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4, respectively. All CUSUM graphs showed an upward slope during the pre-TC period. At the 17th patient (indicated by arrows) in the TC period, a downward inflection was observed and a downward slope was observed after 17th case (Figs. 1–4).

RESULTS

- To our knowledge, this is the first study to illustrate the learning curve associated with REBOA using CUSUM analysis. The results indicated that the quality of the REBOA procedure improved. The accumulation of experience with the REBOA procedure may enhance performance. Additionally, we believe that the establishment of trauma centers plays an important role in improving the skill and knowledge of faculty and the number of dedicated facility members, which helps improve the quality of the procedure. CUSUM-based monitoring appears to be useful for the REBOA procedure. REBOA is generally performed in extremely rare situations; therefore, achieving proficiency may be difficult. We believe that the outcomes, mortality rate, and aortic occlusion time are potential indicators of the performance of REBOA. An improvement in aortic occlusion time represents prompt hemostasis and the reduction of ischemia.

- Although enthusiasm has grown regarding the use of REBOA for trauma patients with severe hemorrhage, the procedure’s indications and outcomes, including mortality and morbidity, are controversial [6,12]. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis [6], REBOA was associated with lower mortality than ED thoracotomy, whereas no significant difference was observed between patients who underwent REBOA and those who did not. However, this meta-analysis included a limited number of studies (three and five studies comparing REBOA with ED thoracotomy and non-REBOA, respectively), and all included studies were observational. Thus, the exact effect size is unclear due to substantial selection bias. In a retrospective cohort study using the American College of Surgeons National Trauma Database with propensity score matching [7], REBOA was associated with increased mortality, even after adjustment for measured confounders. The authors reported that REBOA was not associated with acute kidney injury or amputation. In our study, only one patient underwent hemodialysis, and none underwent lower extremity amputation. However, these complications are rare. In a recent review on the opinions of trauma providers regarding REBOA, interest was revealed to be widespread, but the need for training persists [13]. Thus, clinical results may need to be re-evaluated after the teaching of technical skills and dissemination of information regarding indications and complications. In our study, all patients with initial SBP levels that could not be assessed died. Further study is warranted for such patients, and more rigorous indication may be needed.

- In a 5-year retrospective analysis based on the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma’s Aortic Occlusion in Resuscitation for Trauma and Acute Care Surgery (AORTA) multi-institutional database [8], a center was defined as high-volume if it had more than 30 cases of REBOA over 5 years, low-volume if it had less than 10, and average-volume if it had 11 to 30 cases. The results indicated that survival was higher in high-volume centers than in low-volume ones [8]. From this perspective, our trauma center can be regarded as high-volume because over 5 years, REBOA was performed for 31 patients. Moreover, we used CUSUM analysis to demonstrate that the performance of the REBOA procedure improved after the 17th case. We believe that this study provides new insights for trauma surgeons. REBOA is a bridge procedure used prior to achieving definitive hemostasis. REBOA requires the prompt availability of medical staff and facilities such as a proficient trauma or vascular surgeon, well-trained nurses, point-of-care ultrasonography and portable X-ray equipment, a vascular access device, a trauma bay, an operating room, an interventional radiology room, and a REBOA kit [4]. Harmoniously organizing these components may be time-consuming. At our trauma center, more than 17 cases were needed to achieve proficiency in the REBOA procedure. We believe that assigning dedicated medical staff and facilities via trauma centers may promote such improvements. Such organization may enhance the proficiency of staff and the effectiveness of the overall trauma system. Trauma surgeons may also improve their understanding of REBOA after a trauma center has been established.

- Our study had several limitations. First, it was retrospective and observational. However, no randomized controlled trials have been conducted regarding REBOA. Second, the single-cohort nature and small sample size of the study are crucial limitations, and larger-scale prospective studies are needed. Third, the most important limitation is the variation in the skill and experience of the surgeons. This may have impeded consistency in proficiency in the REBOA procedure. However, investigation at the hospital level is crucial because REBOA requires a multidisciplinary approach. Fourth, conventional statistical methods showed no statistically significant difference between the pre-TC and TC periods, although mortality and occlusion time differed non-significantly between them. This lack of significant findings may have been due to the small number of patients (n=31) studied. However, acquiring sufficient datasets is very difficult because REBOA is rarely performed. Therefore, CUSUM monitoring is a potential alternative method. Fifth, the contribution of the establishment of trauma centers to the improvement in REBOA outcomes remains ambiguous. Further studies are required to confirm this hypothesis. However, we observed that the performance of the procedure improved after the 17th patient. This may provide meaningful insights to trauma surgeons who wish to begin performing the REBOA procedure. Sixth, we could not perform risk-adjusted CUSUM analysis because of the small sample size. In a previous study, a risk-adjusted CUSUM methodology was used to adjust for individual risk and minimize selection bias based on a multivariable logistic regression model [9,11]. However, such models are statistically unstable when the sample size is small [14]. Future large-scale studies are required. Seventh, we postulated that aortic occlusion time is a surrogate marker of success in REBOA procedures. No evidence is available regarding this issue. However, guidelines recommend balloon deflation as soon as possible [4]. Prolonged occlusion time induces ischemic damage and reducing occlusion time may require a well-organized trauma system and proficient staff. For example, prompt detection of the balloon position, early preparation for surgery, or angioembolization may be needed. We hope that this can provide new insight for researchers. Finally, we initially attempted partial REBOA (5 to 10 mL of balloon inflation) and added fluids according to the patient’s status. However, unfortunately, our medical records included no records of the inflating fluid in some patients. Thus, we could not distinguish partial from total REBOA. We could not identify even intermittent REBOA due to the limited medical records available.

- In conclusion, the performance of the REBOA procedure in terms of mortality and aortic occlusion time improved after the 17th case. CUSUM analysis may be useful for monitoring the procedure when the sample size of the cohort is not sufficient to expect statistical stability. However, further large-scale prospective studies are warranted to confirm the true effect size.

DISCUSSION

-

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data sharing statement

The data of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: HC, WSK; Data curation: all authors; Formal analysis: WSK; Methodology: HC, WSK; Project administration: WSK; Visualization: WSK; Writing–original draft: HC, WSK; Writing–review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

- 1. Cannon JW, Khan MA, Raja AS, et al. Damage control resuscitation in patients with severe traumatic hemorrhage: a practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;82:605–17. PubMed

- 2. Khalid S, Khatri M, Siddiqui MS, Ahmed J. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of aorta versus aortic cross-clamping by thoracotomy for noncompressible torso hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. J Surg Res 2022;270:252–60. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Borger van der Burg BL, van Dongen TT, Morrison JJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in the management of major exsanguination. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2018;44:535–50. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 4. Brenner M, Bulger EM, Perina DG, et al. Joint statement from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS COT) and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) regarding the clinical use of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA). Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2018;3:e000154ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Liu A, Nguyen J, Ehrlich H, et al. Emergency resuscitative thoracotomy for civilian thoracic trauma in the field and emergency department settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Res 2022;273:44–55. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Castellini G, Gianola S, Biffi A, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in patients with major trauma and uncontrolled haemorrhagic shock: a systematic review with meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg 2021;16:41. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. Linderman GC, Lin W, Becher RD, et al. Increased mortality with resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta only mitigated by strong unmeasured confounding: an expanded analysis using the national trauma data bank. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;91:790–7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Gorman E, Nowak B, Klein M, et al. High resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta procedural volume is associated with improved outcomes: an analysis of the AORTA registry. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;91:781–9. ArticlePubMed

- 9. Kang WS, Jo YG, Park YC. Quality improvement of damage control laparotomy: impact of the establishment of a single Korean regional trauma center. World J Surg 2019;43:2814–21. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 10. Noyez L. Cumulative sum analysis: a simple and practical tool for monitoring and auditing clinical performance. Health Care Curr Rev 2014;2:113. Article

- 11. Kim CH, Kim HJ, Huh JW, Kim YJ, Kim HR. Learning curve of laparoscopic low anterior resection in terms of local recurrence. J Surg Oncol 2014;110:989–96. ArticlePubMed

- 12. Joseph B, Zeeshan M, Sakran JV, et al. Nationwide analysis of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in civilian trauma. JAMA Surg 2019;154:500–8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Samuels JM, Sun K, Moore EE, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta: interest is widespread but need for training persists. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;89:e112–6. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Sperandei S. Understanding logistic regression analysis. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2014;24:12–8. ArticlePubMedPMC

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Emergency department laparotomy for patients with severe abdominal trauma: a retrospective study at a single regional trauma center in Korea

Yu Jin Lee, Soon Tak Jeong, Joongsuck Kim, Kwanghee Yeo, Ohsang Kwon, Kyounghwan Kim, Sung Jin Park, Jihun Gwak, Wu Seong Kang

Journal of Trauma and Injury.2024; 37(1): 20. CrossRef - Nonselective versus Selective Angioembolization for Trauma Patients with Pelvic Injuries Accompanied by Hemorrhage: A Meta-Analysis

Hyunseok Jang, Soon Tak Jeong, Yun Chul Park, Wu Seong Kang

Medicina.2023; 59(8): 1492. CrossRef

KST

KST

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite