Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Trauma Inj > Volume 30(4); 2017 > Article

-

Original Article

The Value of X-ray Compared with Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Traumatic Vertebral Fractures - Yang Woo Lee, M.D.1, Jae Ho Jang, M.D.1, Jin Joo Kim, M.D.1, Yong Su Lim, M.D.1, Sung Youl Hyun, M.D.2, Hyuk Jun Yang, M.D.1

-

Journal of Trauma and Injury 2017;30(4):158-165.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20408/jti.2017.30.4.158

Published online: December 30, 2017

- 7,733 Views

- 112 Download

- 2 Crossref

1Department of Emergency Medicine, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, Incheon, Korea

2Department of Trauma, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, Incheon, Korea

- Correspondence to: Jae Ho Jang, M.D., Department of Emergency Medicine, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, 21 Namdong-daero 774beon-gil, Namdong-gu, Incheon 21565, Korea, Tel: +82-32-460-3015, Fax: +82-32-460-3019, E-mail: jhjang@gilhospital.com

• Received: August 22, 2017 • Revised: September 29, 2017 • Accepted: October 12, 2017

Copyright © 2017 The Korean Society of Trauma

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

Purpose

- The purpose of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of X-rays in patients with acute traumatic vertebral fractures visiting the emergency department and to analyze the diagnostic value of X-rays for each spine level.

-

Methods

- We retrospectively analyzed basal characteristics by reviewing medical records of 363 patients with adult traumatic vertebral fractures, admitted to the emergency center from March 1, 2014 to February 28, 2017. We analyzed spine X-rays and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to determine distribution according to the vertebral level, and we evaluated the efficacy of X-rays by comparing discrepancies between X-rays and MRI scans.

-

Results

- For a total of 363 patients, the mean age was 56.65 (20–93) and 214 (59%) were males. On the basis of X-rays, 67 cases (15.1%) were of the cervical spine, 133 cases (30.0%) were of the thoracic spine, and 243 cases (54.9%) were of the lumbar spine. In particular, the thoracolumbar region (T11-L2) was the most common, with 260 cases (58.7%). In X-rays, fractures were the least in the upper thoracic region (T1-T3), whereas MRI scans revealed fairly uniform distribution across the thoracic spine. Sensitivity of X-rays was lowest in the upper thoracic spine and specificity was almost always greater than 98%, except for 94.7% in L1. Positive predictive value was lower in the mid-thoracic region (T4-T9) and negative predictive value was slightly lower in C6, T2, and T3 than at other sites. Diagnostic accuracy of X-rays by vertebral body, transverse process, and spinous process according to fractured vertebral structures was significantly different according to vertebral level.

-

Conclusions

- Diagnostic accuracy of X-rays was lower in the upper thoracic region than in other parts. Further studies are needed to identify better methods for diagnosis considering cost and neurological prognosis.

- Vertebral fractures frequently occur in patients with acute spinal injuries caused by trauma. It may have accompanying damages including limb and pelvic fractures, head injuries, thoracic, abdominal and genitourinary system injuries, affecting treatment [1–3]. Spinal injuries may lead to serious neurological sequelae. In particular, cervical spinal injuries may present symptoms such as limb paralysis, dysuria, dyschezia, and respiratory or circulatory failure, that may lead to life-threatening consequences unlike thoracic or lumbar spinal injuries [4,5]. In addition, recent studies have demonstrated that back disability, increased days of limited activity, and bed days as well as greater mortality are associated with vertebral fractures [6,7]. Despite its severity, vertebral fractures are currently underdiagnosed, and according to a study, only about one third of all vertebral fractures come to clinical attention [8].

- Radiography is typically the first modality used to evaluate the spine after trauma when patients visit the emergency department. An accurate radiography is critical for diagnosis of vertebral fractures. Most of the existing studies on diagnosis of vertebral fractures are limited to non-traumatic pathologic fractures and few studies have been conducted on traumatic fractures. Despite standardization of radiographic reading, in approximately half of hospitalized elderly patients, moderate to severe vertebral fracture could not be diagnosed [9], according to a retrospective study. In a similar multinational prospective study, diagnostic accuracy of X-rays for vertebral fractures was poor with 34% of false negative rating, but all of these studies were conducted on patients with osteoporotic vertebral fractures [10]. Regarding patients with traumatic vertebral injury, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recently used in addition to simple radiography, and here, for not only fractures, but also other diagnoses including soft tissue injury such as muscle, tendon and ligament or spinal cord injury may be detected through MRI [11,12]. However, there is a cost and time constraint to conduct MRI in all trauma patients visiting the emergency department to improve diagnostic accuracy of vertebral fractures.

- The goal of this study is to identify diagnostic accuracy of X-rays in patients with traumatic vertebral fractures visiting the emergency department (ED) and to analyze the diagnostic value of X-rays for each spine level.

INTRODUCTION

- Study population

- This study selected those patients visited the emergency center for 3 years (from March 1, 2014 to Febuary 28, 2017) and retrospectively analyzed their data. Inclusion criteria of subjects in the study are as follows: 1) trauma patients age 18 or older; 2) patients admitted through an emergency center; 3) patients that underwent both X-rays and MRI on vertebrae with fractures; and 4) patients diagnosed with acute vertebral fractures based on MRI readings.

- The following patients were excluded from the study: 1) patients with history of cancer or osteoporosis. In case of osteoporosis, baseline T score of −2.5 SD or less according to conservative criteria [13–15], or patients in preventive medical treatment according to a recent trend were classified as osteoporosis [16,17]; and 2) patients that aborted hospitalization (voluntarily discharged or transferred to another hospital from the ED).

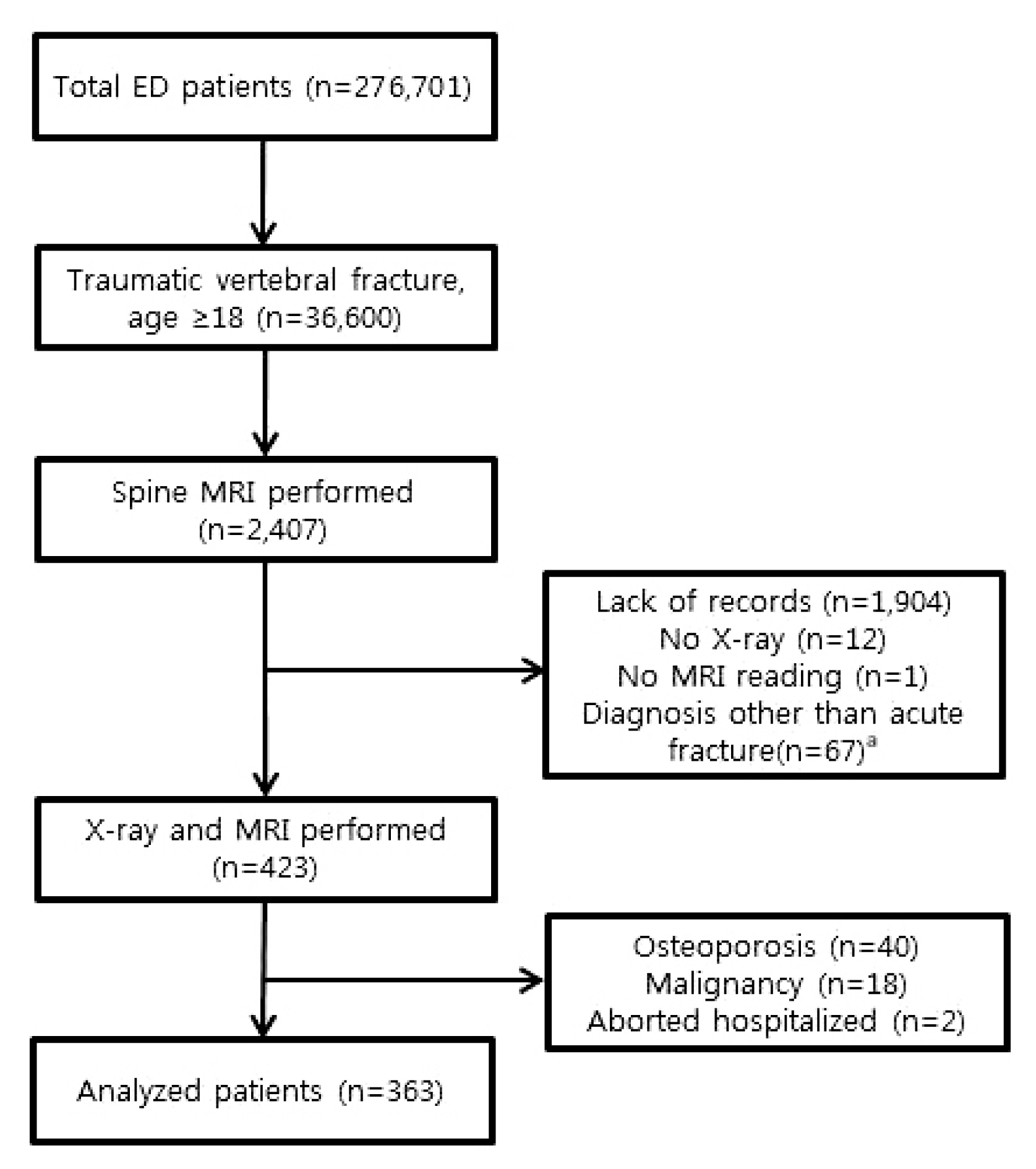

- Of the 2,407 patients underwent spine MRI, 363 patients were finally enrolled in this study, excluding patients who met exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). In terms of these patients, basal characteristics such as age, sex, body weight, vital signs (blood pressure, pulse and respiration rate, etc.) and the level of consciousness Glasgow coma scale (GCS) at the time of ED visit, injury severity score (ISS) presented in the ED and injury mechanisms were analyzed. For diagnosis, we used anteroposterior and lateral radiograph of the vertebrae taken preoperatively. All of radiologic evaluations including X-rays and MRI were performed by a radiologist who was blinded without participating in this study. We analyzed spine X-rays and MRI findings to determine distribution according to vertebral level, and evaluated accuracy of X-rays in the diagnosis of traumatic vertebral fractures by comparing discrepancies between X-rays and MRI findings.

- Statistical analysis

- All calculations were conducted using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and null hypotheses of no difference were rejected if p-values were <0.05. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation. Chi-square test was taken for categorical variables. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated through cross-tabulation analysis.

METHODS

- Regarding a total of 363 patients that participated in this study, mean age was 56.65 (20–93), and 214 patients (59%) were males. Mental status in visit to the ED was 14.71 of GCS on average, and degree of injury was 10.91 on average of ISS. For injury mechanisms, falling was the most common (32%), followed by traffic accidents (30.1%) and slipping (22.9%) (Table 1).

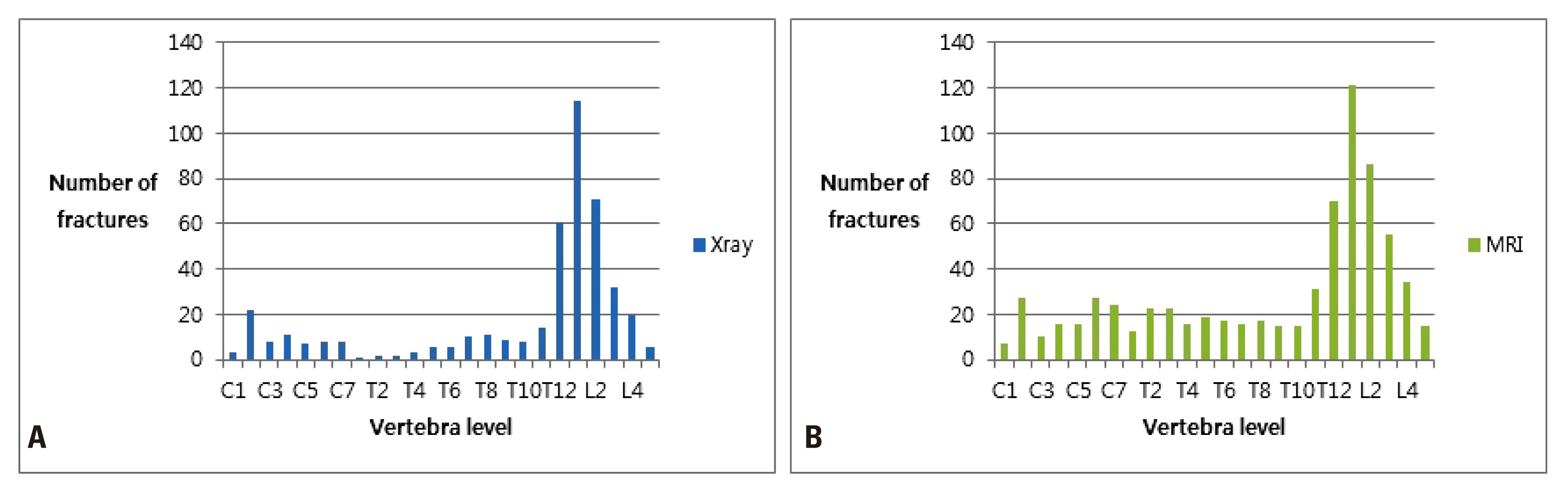

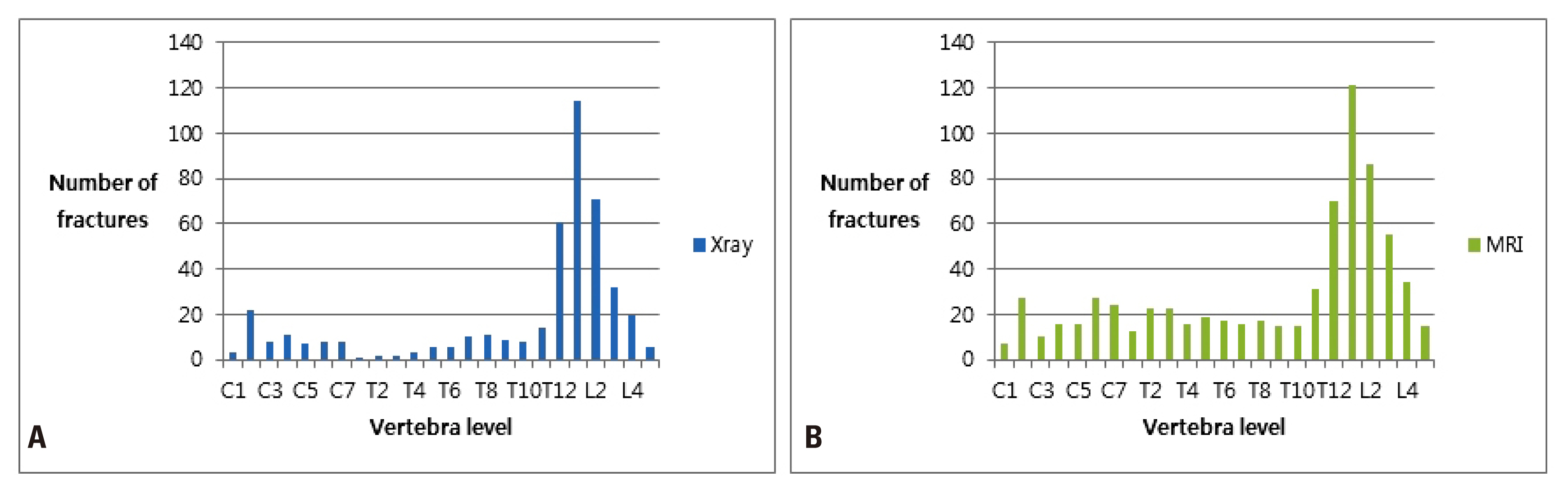

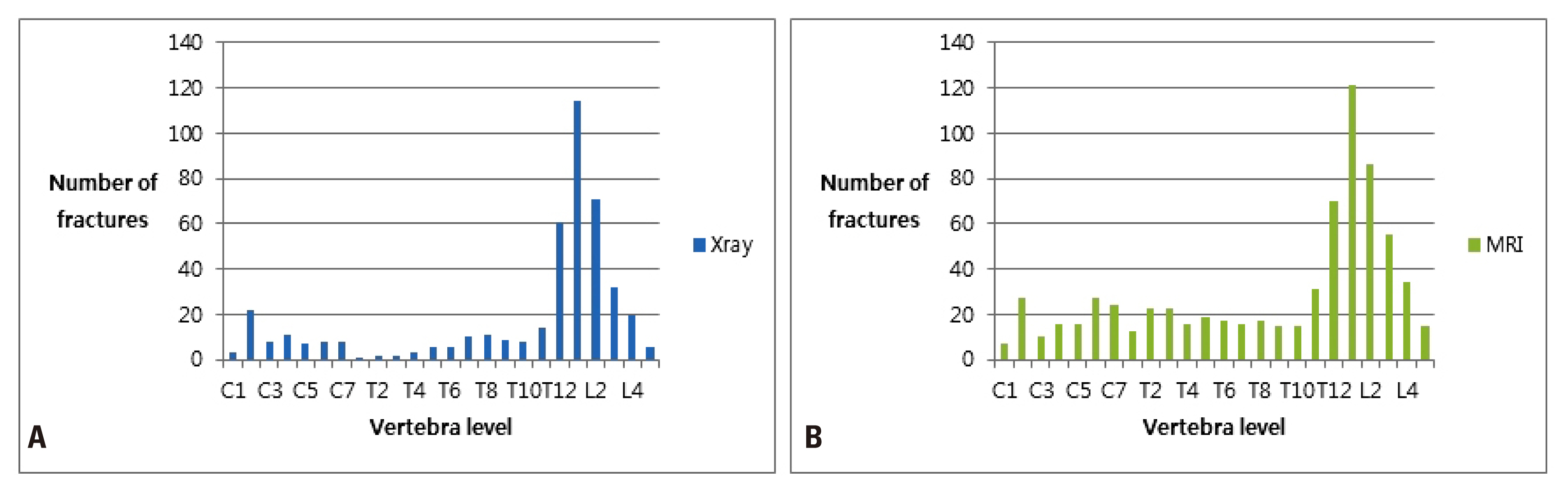

- In X-rays of a total of 363 patients, a total of 443 fractures were found, and in MRI, a total of 713 fractures were identified. Vertebral fractures were divided into cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral fractures according to vertebral level, and also divided into vertebral body fracture, transverse process fracture, spinous process fracture, and pedicle, lamina and articular process fractures according to fractured structures. Distribution by vertebral level in the fracture site was provided in separate graphs for X-rays and MRI, respectively, in Fig. 2. In X-rays, 67 cervical fractures (15.1%), 133 thoracic fractures (30.0%), and 243 lumbar fractures (54.9%) were found in a total of 443 injuries. In particular, 260 fractures occurred in the thoracolumbar region (T11-L2), accounting for 58.7%, most frequently found. In both X-rays and MRI, cases were most frequently found in L1 (114 in X-ray vs. 121 in MRI), followed by L2 and T1. By spinal region, the cervical region had C2 (including the odontoid) fractures most commonly found in X-rays (22 fractures [32.8%]), followed by C4 (11 fractures [16.4%]). While in MRI, C2 and C6 were identical and most frequently found (27 fractures [21.3%]), followed by C7 (24 fractures [18.9%]). In case of the lumbar region, as described above, fracture cases in L1 were most frequently found, and the number of fractures was decreased in order of L2, L3, L4, and L5 in both X-rays and MRI. Conversely, fracture cases were most rarely found in the upper thoracic region (T1-T3) in X-rays that had the most significant discrepancy between X-rays and MRI, whereas relatively even distribution was revealed throughout the thoracic region in MRI (Fig. 2).

- Sensitivity of X-rays on traumatic vertebral fractures varied by region, but it was the lowest in the upper thoracic spine. Specificity was almost always 98% or more except for 94.7% in L1. Positive predictive values were low in the mid-thoracic region (T4 to T9), and negative predictive values were almost always more than 90%, but it was the lowest in C6, T2 and T3 with a slight difference (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

- Diagnostic values of X-rays by fractured vertebral structures are described in Table 3. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of X-ray were identified in each vertebral body fracture, transverse process fracture, and spinous process fracture. Since the number of transverse process fractures was small in cervical and thoracic regions, transverse process fractures were analyzed only for fractures in the lumbar spine. As a result, sensitivity was generally lower compared to entire vertebral fractures or vertebral body fractures, with L1 the highest (50%) and L5 the lowest (14.3%). PPV was generally lower, and specificity and NPV were adjacent to 98% or higher. Spinous process fractures were analyzed only for fractures in the cervical spine due to fewer incidences in the thoracic and lumbar regions. Regarding spinous process fractures occurring from C2 to C7 except C1 (Atlas) that have a different anatomical structure, diagnostic values of X-rays revealed significant difference according to vertebral level. All of the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were low in C2 (50%), and were relatively higher in C3 and C4. Sensitivity from C5 to C7 was lower than 40%, but specificity and NPV were higher than 95% (Table 3).

RESULTS

- When looking at distribution by vertebral level in the fracture region, occurrence in the lumbar region was most commonly found in X-rays and MRI. Particularly, 58.7% of all vertebral fractures found on X-rays occurred in the thoracolumbar region (T11-L2), similar to previous studies on patients with traumatic vertebral fractures [18,19]. In the cervical region, C2 was most frequently found in X-rays, and in MRI, C2 and C6 were identically commonly found, also like previous studies [20–22]. In case of the lumbar region, the number of fractures was the largest in L1, and was decreased as it was close to the sacral region. No occurrence of fractures in sacral region was found in X-rays, and in MRI, the accurate level of sacrum was not identified even if the fracture was observed. Thus, they were not separately analyzed in this study. In case of the thoracic region, the degree of diagnostic discrepancy between X-rays and MRI was the largest. Frequency was the lowest in the upper thoracic region for X-rays, whereas relatively even distribution was found throughout the thoracic region for MRI.

- In this study, the diagnostic value of X-rays for traumatic vertebral fractures was diverse by region, but characteristically, diagnostic accuracy was low in the upper thoracic spine compared to other regions. As with similar results, van Beek et al. [23] reported that they missed 22% of diagnoses on X-rays in 23 patients with traumatic upper thoracic vertebral fractures, and Hugo and Dunn [24] also reported that that they missed 22% of diagnoses on X-rays in 33 patients with traumatic upper thoracic vertebral fracture. In addition, Brandser and el-Khoury [25] stated that the upper 3 to 4 thoracic vertebrae are often poorly demonstrated on a standard lateral film due to overlying soft tissues of the upper chest and shoulders. Bohlman [26] drew attention to unique features of trauma involving the upper thoracic spine and noted that due to stiffness, considerable trauma is necessary to cause fractures or fracture-dislocations in the upper thonacic spine, and due to the narrow thoracic spinal canal and relatively sparse blood supply in central thoracic spine, injuries of the spinal cord are frequently associated with injuries of the upper thonacic spine, and in case of neurological injury, it is usually severe. In addition, Bradford et al. [27] reported that multiple thoracic wedge compression fractures are the primary exception to the rule that pure flexion-compression injuries do not cause acute neurological loss. Together, in interpreting results of this study of the difference in the incidence of fractures between X-rays and MRI in the thoracic spine and of the low diagnostic accuracy of X-rays in the upper thoracic region, considering unique features of trauma involving upper thoracic spine and the difficulty of diagnosing fracture by X-rays in this region presented in other studies, the high index of suspicion should be maintained in patients with trauma involving upper thoracic spine regardless of fractures found in X-rays. And we suggest that if a patient complains of persistent pain in this region or if a severe injury mechanism such as a fall or a traffic accident occurred regardless of the degree of pain, additional examinations such as computed tomography or MRI should be considered more aggressively than other regions [23,24,28].

- Vertebral body fracture, when analyzed according to the fractured vertebral structure, revealed similar patterns of results compared to results for entire vertebral fractures identified earlier, which caused by the fact that frequency of vertebral body fracture was most frequently found in vertebral fractures. Goldberg et al. [22] stated that vertebral body and odontoid fractures were significant because these fractures account for the largest fraction of injuries to specific part of the vertebrae and they are frequently related to spinous instability in the study conducted on 818 patients with radiographic cervical spine injuries whereas spinous and transverse process fractures were often clinically insignificant and unlikely to be associated with spinous instability. In this study, the transverse process fracture was analyzed only in the lumbar region, and diagnostic accuracy of X-rays was lower than that of the entire vertebral fracture or vertebral body fracture described above. Regarding the spinous process fracture, analysis was conducted only in the cervical spine. The diagnostic value of X-rays in fractures occurring from C2-C7 except C1 (Atlas) that had different anatomical structure revealed a significant difference by level. This was attributable to anatomical and structural characteristics of the cervical spine as well as various injury mechanisms of the cervical spine associated with it [29,30]. Other vertebral fractures such as pedicle, lamina, and articular process fractures were not analyzed separately due to the limited number of occurrence.

- As for limitations of this study, bone mineral density was not considered. Due to incompletion of clinical records, few patients identified their bone mineral density (BMD) testing before hospitalization. Considering that BMD of patients functioned as the greatest variable in a number of studies conducted in patients with non-traumatic vertebral fractures, it was disappointing that BMD could not be identified in our study. Further studies are needed to analyze how traditional risk factors for osteoporosis, such as age and BMD, impact traumatic vertebral fractures. Another limitation is that regions taken by X-rays and the regions taken by MRI were not matched 1:1 in all cases of the subjects. X-rays were often taken in other vertebral regions with and without fractures, but MRI was often taken in one or two areas in which fractures occurred. Therefore, the diagnostic value of X-rays as a screening tool was underestimated. In addition, in terms of fractures occurring in one vertebral level, two or more vertebral structures were often fractured, and adjacent vertebral fractures in higher and lower levels were often found. These findings were not identified by X-rays but often identified by MRI. In this study, diagnostic value of X-rays was analyzed with absence or presence of fractures in the applicable level, but in the future, a study on the clinical degree of patient prognosis and different treatment in case of fractures of complex region and accompanying fractures in the adjacent vertebral level. Economic aspects relative to the cost of MRI was not considered. The issue of the examination fee for MRI was not solved, and it cannot be termed a universally appropriate examination for spinal trauma patients. The most significant issue is that, when considering the severity of spinal injuries, it cannot be judged simply by vertebral fractures, but a number of diagnoses such as spinal cord injury or ligament injury should be considered as well. Considering the neurologic prognosis of the patient, the clinical significance of X-rays or MRI could not be confined solely to vertebral fractures.

DISCUSSION

- Diagnostic accuracy of X-rays was lower in the upper thoracic region than other regions, indicating the necessity of additional examinations such as MRI that is more urgent in this region than others. In the future, it is necessary to conduct studies to seek better methods for diagnosis, and consider cost and neurologic prognosis in diagnosis of traumatic spinal injuries.

CONCLUSION

Fig. 1This figure shows study flow diagram of study population. The diagnosis was based entirely on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) readings. For example, if a vertebral fracture was found on an X-ray or computed tomography scan, but a diagnosis other than an acute fracture was made on an MRI reading (suspicious fracture, old healed fracture, strain, Sprain, contusion, ligament injury, etc.) were excluded from the study (n=67). ED: emergency department. aDiagnosed as sprain and contusion.

Fig. 2This figure shows the distribution of the fracture site according to the vertebral level for both X-ray and MRI as a separate graph. (A) X-ray, (B) MRI. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Fig. 3This graph shows the sensitivity and specificity of X-ray according to the vertebral level for the diagnosis of traumatic vertebral fractures. The overall value of X-ray for the diagnosis of traumatic vertebral fractures, including other values such as positive predictive value and negative predictive value, is shown in Table 2.

Table 1Patient characteristics

Table 2Diagnostic value of X-ray to detect vertebral fractures

Table 3Diagnostic value of X-ray to detect vertebral fractures (according to fractured vertebral structures)

- 1. Bedbrook GM. Treatment of thoracolumbar dislocation and fractures with paraplegia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1975;(112):27–43.

- 2. Burke D, Murray DD. The management of thoracic and thoraco-lumbar injuries of the spine with neurological involvement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1976;58:72–8.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Riggins RS, Kraus JF. The risk of neurologic damage with fractures of the vertebrae. J Trauma 1977;17:126–33.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Kraus JF, Franti CE, Riggins RS. Neurologic outcome and vehicle and crash factors in motor vehicle related spinal cord injuries. Neuroepidemiology 1982;1:223–38.Article

- 5. Wagner FC Jr, Cheharzi B. Neurologic evaluation of cervical spinal cord injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1984;9:507, ArticlePubMed

- 6. Huang C, Ross PD, Wasnich RD. Vertebral fracture and other predictors of physical impairment and health care utilization. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2469–75.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Ross PD. Clinical consequences of vertebral fractures. Am J Med 1997;103:S30–42; discussion 42S–3, Article

- 8. Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd. Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985–1989. J Bone Miner Res 1992;7:221–7.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Gehlbach S, Bigelow C, Heimisdottir M, May S, Walker M, Kirkwood JR. Recognition of vertebral fracture in a clinical setting. Osteoporos Int 2000;11:577–82.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 10. Delmas PD, van de Langerijt L, Watts NB, Eastell R, Genant H, Grauer A, et al. Underdiagnosis of vertebral fractures is a worldwide problem: the IMPACT study. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20:557–63.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Tracy PT, Wright RM, Hanigan WC. Magnetic resonance imaging of spinal injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14:292–301.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Flanders AE, Schaefer DM, Doan HT, Mishkin MM, Gonzalez CF, Northrup BE. Acute cervical spine trauma: correlation of MR imaging findings with degree of neurologic deficit. Radiology 1990;177:25–33.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Burger H, de Laet CE, van Daele PL, Weel AE, Witteman JC, Hofman A, et al. Risk factors for increased bone loss in an elderly population: the Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:871–9.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 14. World Health Organization (WHO). Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group [meeting held in Rome from 22 to 25 June 1992[Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 1994 [cited 2017 Aug 22]. Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39142.

- 15. Wainwright SA, Phipps KR, Stone JV, Cauley JA, Vogt MT, Black DM, et al. A large proportion of fractures in postmenopausal women occur with baseline bone mineral density T-score. J Bone Miner Res 2001;16:S155.

- 16. Black DM. Revision of T-score BMD diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporos Int 2000;11:S58.

- 17. Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, Wehren LE, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1108–12.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Leucht P, Fischer K, Muhr G, Mueller EJ. Epidemiology of traumatic spine fractures. Injury 2009;40:166–72.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Cho NS, Lee KU, Choi BN. Clinical analysis of traumatic spinal fractures. J Trauma Inj 1997;10:88–94.

- 20. Ryan MD, Henderson JJ. The epidemiology of fractures and fracture-dislocations of the cervical spine. Injury 1992;23:38–40.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Walter J, Doris PE, Shaffer MA. Clinical presentation of patients with acute cervical spine injury. Ann Emerg Med 1984;13:512–5.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Goldberg W, Mueller C, Panacek E, Tigges S, Hoffman JR, Mower WR, et al. Distribution and patterns of blunt traumatic cervical spine injury. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:17–21.ArticlePubMed

- 23. van Beek EJ, Been HD, Ponsen KK, Maas M. Upper thoracic spinal fractures in trauma patients - a diagnostic pitfall. Injury 2000;31:219–23.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Hugo D, Dunn RN. Proximal thoracic spine fractures: a dangerous blind spot. SA Orthop J 2011;10:30–5.

- 25. Brandser EA, el-Khoury GY. Thoracic and lumbar spine trauma. Radiol Clin North Am 1997;35:533–57.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Bohlman HH. Treatment of fractures and dislocations of the thoracic and lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985;67:165–9.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Bradford DS, Akbarnia BA, Winter RB, Seljeskog EL. Surgical stabilization of fracture and fracture dislocations of the thoracic spine. Spine 1977;2:185–96.Article

- 28. el-Khoury GY, Whitten CG. Trauma to the upper thoracic spine: anatomy, biomechanics, and unique imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993;160:95–102.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Nightingale RW, Winkelstein BA, Knaub KE, Richardson WJ, Luck JF, Myers BS. Comparative strengths and structural properties of the upper and lower cervical spine in flexion and extension. J Biomech 2002;35:725–32.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Cusick JF, Yoganandan N. Biomechanics of the cervical spine 4: major injuries. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2002;17:1–20.ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- A novel radiological assessment to identify acute vertebral compression fractures: A pilot observational study

Keisuke Tsuruta, Toru Ueyama, Tomoo Watanabe, Yasunori Kobata, Kenichi Nakano, Hidetada Fukushima

Acute Medicine & Surgery.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Forward Bending in Supine Test: Diagnostic Accuracy for Acute Vertebral Fragility Fracture

Chan-Woo Jung, Jeongik Lee, Dae-Woong Ham, Hyun Kang, Dong-Gune Chang, Youngbae B. Kim, Young-Joon Ahn, Joo Hyun Shim, Kwang-Sup Song

Healthcare.2022; 10(7): 1215. CrossRef

KST

KST

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite