Effects of Trauma-Related Shock on Myocardial Function in the Early Period Using Transthoracic Echocardiography

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The present study aimed to analyze the effect of trauma-related shock on myocardial function in the early stages of trauma through transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) findings.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review and analysis of the medical records of patients aged ≥18 years who were evaluated by TTE within 2 days of admission for trauma-related shock (n=72). Patients were selected from a group of 739 patients admitted with trauma-related shock between January 2014 and December 2016.

Results

The incidence rate of myocardial dysfunction in the left ventricle (LV) was 6.8% (5/72), with rates of 7.7% (4/52) in the thoracic injury group and 5.0% (1/20) in the non-thoracic injury group. In the diastolic function of LV, relaxation abnormality was present in 55.8% (29/52) of patients in the thoracic injury group and 50% (10/20) of patients in the non-thoracic injury group.

Conclusions

This study may suggest that traumatic shock without thoracic injury may influence myocardial function in the early stages after trauma. Therefore, evaluation of myocardial function may be needed for patients experiencing shock after trauma, regardless of the presence of thoracic injury.

INTRODUCTION

Blunt traumatic cardiac injury, or myocardial contusion, is histologically defined as a bruise in the myocardium. Postmortem studies by Turan et al. [1] found cardiac injuries in 11.9% (190/1,597) of cases of individuals who died by blunt trauma. Contusions were found in the both atria, (19 [10%] right atrium, and five [2.6%] left atrium) as well as both ventricles (right 23 [12.1%] right ventricle and 17 [8.9%] left ventricle) [1]. However, in living individuals, there is no standard test for diagnosing myocardial contusion, and currently available diagnostic tools have limitations in making a diagnosis. This holds true particularly when conclusive tests such as surgical interventions or postmortem autopsy of the injuries are absent. The incidence rate of myocardial contusion was reported to range from 3% to 56% according to the diagnostic criteria and evaluation tools [2]. The incidence of myocardial contusion based on the findings of transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was reported to be approximately 20% in blunt chest trauma [3]. Myocardial injury could be caused by either direct impact to the chest, or as a secondary injury due to trauma-related additional damage such as hypoxia, hypovolemic shock, and multiple injuries, consequently affecting the myocardium structure and function [4]. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are released during trauma and act as a mediator, play an important role in various processes, ranging from systemic inflammatory response syndrome after trauma to the structural and functional impairment of cardiomyocytes and cardiac dysfunction [5-7]. Thus far, the incidence and effects of myocardial injury by direct damage, accompanied by thoracic injury, and by indirect damage due to shock after trauma in the early period are not well studied.

The present study aimed to analyze the effects of shock after trauma on myocardial function in the early stages, especially in the presence or absence of thoracic injury, through TTE.

METHODS

Study design and patients

This study was a retrospective review of the medical records of blunt trauma patients in a single institution between January 2014 and December 2016. The protocol of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. GBIRB2019-044). The informed consent was waived from IRB due to the retrospective design. Patients aged ≥18 years who had a trauma-related shock which initial systolic blood pressure (SBP) of ≤90 mmHg on arrival at our center were included. We excluded patients who were examined 3 days after admission or for whom we were unable to obtain adequate quality images except for diastolic function evaluation on echocardiography. Patients with pre-existing cardiologic problems who did not have comparable previous echocardiography data were also excluded. Echocardiograms were formally analyzed and interpreted by cardiologists. With regard to echocardiographic findings, systolic function was classified as normal, depressed (<55%), and hyperdynamic (>70%) based on left ventricle (LV) ejection fraction, and diastolic function was classified as normal, relaxation abnormality, or indeterminate.

Demographic data like age, gender, mechanism of injury, and echocardiographic data were extracted from the medical records of the institution. Severity scores, including the Injury Severity Score (ISS) and abbreviated injury scale, were extracted from the institutional trauma registry.

Patients were divided into Group A, which included only those who had thoracic injury, and Group B, which included only those who had no thoracic injury. We reviewed patients’ demographic data, mechanism of injury, severity of the injury, and echocardiography findings.

Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.0.0. Demographic data were reported as frequency and proportion of qualitative variables. Descriptive statistics were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables with non-normal distributions. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

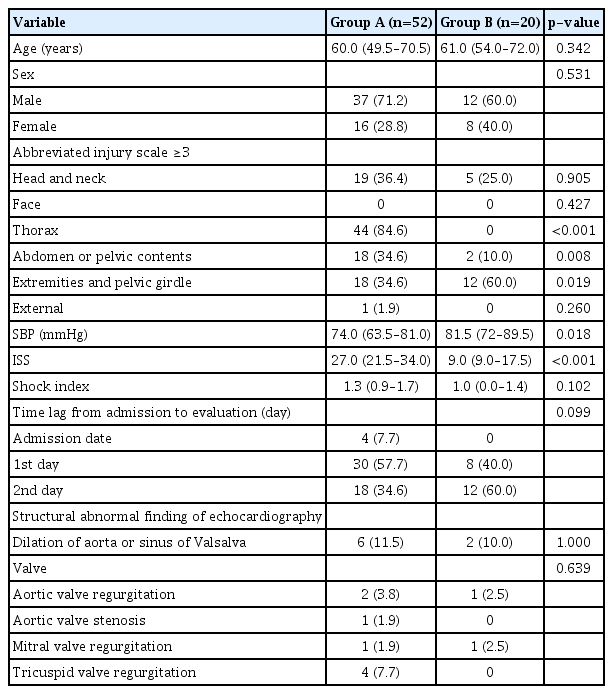

A total of 9,340 patients visited our center during the study period; among them, 739 presented with shock (SBP ≤90 mmHg) on arrival. The incidence rate of traumatic shock in our institution was 7.91% (739/9,340) during the study period. Among them, 72 were evaluated using TTE within 2 days after admission. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Among the 72 patients, 52 were included in Group A and 20 were included in Group B.

Table 2 shows a comparison of demographic data and clinical characteristics between the two groups. Median patient age was 60.0 years in Group A and 61.0 years in Group B, showing a non-significant difference (p=0.342). Males and females accounted for 37 (71.2%) and 15 (28.2%) in Group A and 12 (60.0%) and eight (40.0%) in Group B, which also showed a non-significant difference (p=0.531). Median SBP was 74 mmHg in Group A and 81.5 mmHg in Group B (p=0.018). The median value of ISS was 27.0 versus 9.0, which showed a significant difference (p<0.001). The shock index was 1.3 versus 1.0, which showed a non-significant difference (p=0.102). Furthermore, 6.8% (five of 72) of them had depressed function in their systolic function of LV.

Table 3 shows a comparison of the functional parameters of LV function and specific findings between the two groups based on TTE findings. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in systolic and diastolic function evaluations using echocardiography.

DISCUSSION

Blunt cardiac injury, also called myocardial contusion, which refers to a bruise in the cardiac muscle after blunt chest trauma, could be explained by the mechanical impact on the heart. The conclusive tests for myocardial contusion are autopsy or surgical findings for cardiac injury. Numerous studies on myocardial contusion have been related to chest trauma due to multiple trauma [1,3,8,9]. According to literature data, cardiac injury after multiple trauma is associated with poor patient outcomes [10]. However, despite using the term “myocardial contusion” or “myocardial injury,” the symptoms and signs widely range from being asymptomatic to fatal destruction of the heart. Therefore, there is no standard test for diagnosing myocardial contusion in patients who do not undergo surgery. To evaluate and estimate myocardial contusion or myocardial injury, several studies have proposed and reported outcomes by analyzing combinations of diagnostic tools such as electrocardiography, biomarkers such as troponin I and T, TTE, or transesophageal echocardiography [9,11-13].

A myocardial contusion produces only mild clinical presentations, such as palpitation or precordial pain. Histologically, a myocardial contusion is characterized by intramyocardial hemorrhage, edema, and necrosis of myocardial muscle cells that presents similarly to that in acute myocardial infarction [14,15].

However, since the recognition of DAMPs, indirect injury to myocardial function has been reported in several studies [4,16,17]. Several studies have investigated the relationship between cardiomyopathy and specific trauma [7,18,19]. Even after resuscitation, combined effects such as ischemia-reperfusion, acidosis, hypoxemia, and hypovolemia, which are known to induce cell injuries, might result in remote organ dysfunction [17]. For example, Matheson et al. [20] identified secondary injury to lung function following hemorrhagic shock using DAMPs. In several animal experimental studies, traumatic hemorrhagic shock has been proven to cause cardiac injury and dysfunction as an indirect consequence of trauma and hemorrhage [6,21,22].

There are several studies about the impact of DAMPs on myocardial function in non-traumatic cases. Multiple DAMPs (e.g., heat shock proteins, high mobility group box-1 [HMGB-1], adenosine triphosphate, nuclear and mitochondrial DNA [mtDNA], and RNA) play a role in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. DAMP activation may eventually lead to reperfusion-induced cardiac damage [23-26]. Weber et al. [27] suggest that resultant structural alterations in the heart might be consequences of the complementary events: DAMP activation, the release of extracellular histones, and systemic TNF elevation.

Like HMGB-1, DAMPs are released within 30 minutes after trauma, reach their peak within 6 hours, and are maintained for at least 24 hours. Plasma levels of DAMPs correlate with the severity of the injury, organ failure, and mortality [5].

Bahar et al. [3] reported a 23.5% incidence rate of cardiac contusion based on TTE findings in blunt chest trauma. Vukmir et al. [16] reported abnormal echocardiographic findings in 37.5% of trauma patients who underwent refractory hypotension. Gawande et al. [4], based on autopsy in their study, reported that subendocardial hemorrhages occurred in 13.6% of patients who had no direct cardiac injury when evaluated clinically. In addition, in their study, they reported notable microscopic changes such as congestion and interstitial edema from the 4- to 12-hour survival period and remained until 2 to 3 weeks of survival.

In the present study, only the results of within 2 days of hospitalization were included to evaluate the effect of shock after trauma on myocardial function in the early period. Unlike the study by Gawande et al. [4], patients in this study were clinically evaluated using TTE, and there was no histological evaluation of the myocardium. This study was conducted with patients who had less severe injuries and were less affected by trauma-related shock compared with other studies in which postmortem examination was conducted. Therefore, a direct comparison of the results of these two studies may not be appropriate.

The incidence rate of myocardial dysfunction in the LV was 6.8% (5/72), which were 7.7% (4/52) and 5.0% (1/20) in the thoracic injury group and the non-thoracic injury group, respectively. In the diastolic function of the LV, there was no statistically significant difference, and relaxation abnormality was present in 55.8% (29/52) in the thoracic injury group and 50% (10/20) in the non-thoracic injury group. Diastolic dysfunction after trauma and trauma-related shock has been inconsistently studied; therefore, we could not definitively relate any observed myocardial dysfunction, especially diastolic dysfunction to secondary injury to the myocardium, in this study. However, the incidence of myocardial diastolic dysfunction was high, regardless of the presence of the thoracic injury. These findings may suggest a relationship between myocardial injury and the effects of shock after trauma without thoracic injury. Since echocardiography is generally recommended when blunt cardiac injury is suspected, echocardiography is not typically performed in cases without thoracic injury.

There are several limitations to this study. First, there are inherent limitations associated with the retrospective design. Second, the small sample size was concerning. Third, this study included patients with blunt trauma, but there was no evaluation of the impact of specific organ injury on myocardial function. Fourth, this study was designed for traumatized patients with shock on arrival to the hospital, and the duration or classification of shock or resuscitation was not evaluated. Therefore, patients who were included in this study possibly had a less severe condition than those who did not survive until echocardiography evaluation.

CONCLUSION

Despite these limitations in evaluating the clinical findings, this study may suggest that traumatic shock without thoracic injury may influence myocardial function in the early stages after trauma. Therefore, evaluation of myocardial function may be needed for patients experiencing shock after trauma, regardless of the presence of thoracic injury. However, the scope of this study was limited to evaluating the impact of trauma-related shock on myocardial function primarily during the early period of recovery. Thus, further studies are warranted to establish acceptable management for the effects of shock after trauma on myocardial function.