Angioembolization performed by trauma surgeons for trauma patients: is it feasible in Korea? A retrospective study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Recent advancements in interventional radiology have made angioembolization an invaluable modality in trauma care. Angioembolization is typically performed by interventional radiologists. In this study, we aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of emergency angioembolization performed by trauma surgeons.

Methods

We identified trauma patients who underwent emergency angiography due to significant trauma-related hemorrhage between January 2020 and June 2023 at Jeju Regional Trauma Center. Until May 2022, two dedicated interventional radiologists performed emergency angiography at our center. However, since June 2022, a trauma surgeon with a background and experience in vascular surgery has performed emergency angiography for trauma-related bleeding. The indications for trauma surgeon–performed angiography included significant hemorrhage from liver injury, pelvic injury, splenic injury, or kidney injury. We assessed the angiography results according to the operator of the initial angiographic procedure. The term “failure of the first angioembolization” was defined as rebleeding from any cause, encompassing patients who underwent either re-embolization due to rebleeding or surgery due to rebleeding.

Results

No significant differences were found between the interventional radiologists and the trauma surgeon in terms of re-embolization due to rebleeding, surgery due to rebleeding, or the overall failure rate of the first angioembolization. Mortality and morbidity rates were also similar between the two groups. In a multivariable logistic regression analysis evaluating failure after the first angioembolization, pelvic embolization emerged as the sole significant risk factor (adjusted odds ratio, 3.29; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–10.33; P=0.041). Trauma surgeon–performed angioembolization was not deemed a significant risk factor in the multivariable logistic regression model.

Conclusions

Trauma surgeons, when equipped with the necessary endovascular skills and experience, can safely perform angioembolization. To further improve quality control, an enhanced training curriculum for trauma surgeons is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Traumatic injury remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1,2]. In cases of life-threatening hemorrhage, rapid and effective interventions are critical for patient survival. Historically, bleeding in these situations has been controlled surgically, either through direct suturing or ligation [3,4]. Moreover, in the era of damage control, techniques such as perihepatic packing or pelvic packing have played important roles in hemorrhage control [4]. Nevertheless, surgical management is invasive and associated with morbidity [5–7]. With recent advancements in interventional radiology and its tools, angioembolization has become a valuable addition to the trauma surgeon’s armamentarium [5,6]. Interventional radiology offers several advantages over surgery, such as being less invasive and often eliminating the need for general anesthesia, thereby reducing morbidity [5,6]. Angioembolization entails the targeted occlusion of blood vessels by introducing embolic agents to either temporarily or permanently halt bleeding. Its use has expanded to the management of hemorrhage in various traumatic scenarios, from pelvic fractures to solid organ injuries [8–11].

As the use of angioembolization at trauma centers continues to expand, it is essential to thoroughly evaluate the procedure’s role, efficacy, and safety. In trauma care, rapid responses are paramount [12]. Nonetheless, the availability of interventional radiologists—who are expected to be on-call for emergency angiographic procedures at all times—is limited in real-world settings. The constant demand for immediate interventions for trauma patients exerts significant pressure on these specialists, and attending trauma surgeons often find themselves dependent on the decisions and actions of interventional radiologists. To address this challenge, in 2022, Jeju Regional Trauma Center, Cheju Halla General Hospital (Jeju, Korea) began offering emergency angioembolization procedures performed by a trauma surgeon. With their intimate involvement in the initial assessments and stabilization of patients, trauma surgeons are potentially better positioned to make timely decisions regarding the necessity and timing of angioembolization.

Objectives

In this study, we aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of emergency angioembolization performed by a trauma surgeon. We also sought to compare outcomes between procedures carried out by trauma surgeons and those by interventional radiologists.

METHODS

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cheju Halla General Hospital (No. 2023-L17-01). The requirement for informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

Study design and setting

We reviewed data from the Korean Trauma Database covering the period from January 2020 through June 2023 at our trauma center. We identified patients with trauma who had undergone emergency angiography due to significant posttraumatic hemorrhage. We excluded patients who underwent their first angiography more than 72 hours after admission, those who underwent non–trauma-related procedures, such as percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage, coronary angiography, or stent placement for aortic aneurysm, and those who underwent interventions on the brain or inferior vena cava filter placement for thromboembolism prevention.

We collected and analyzed data on patient demographics and clinical information, including injury mechanism, age, sex, laboratory findings, vital signs, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, Injury Severity Score (ISS), Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score, transfusion details, angiography findings, use of embolic agents (e.g., Gelfoam or coils), mortality, and morbidity (e.g., postangiographic rebleeding or infection).

At our trauma center, two dedicated interventional radiologists performed emergency angiography until May 2022. One of these radiologists has approximately 25 years of experience, and the other has 7 years of experience in interventional radiology. From June 2022 onwards, a trauma surgeon with a background in vascular surgery began conducting emergency angiography for trauma-related hemorrhages, specifically those due to liver injury, pelvic injury, splenic injury, or kidney injury. Injuries of the lumbar artery, intercostal artery, branch of femoral artery, scrotal artery, inferior vena cava, or subclavian artery injuries were categorized as “other injuries.” One of our trauma surgeons previously specialized in vascular surgery. Before the establishment of the trauma center, he practiced as a vascular surgeon. Now, he is fully committed to his role as a trauma surgeon with us. We evaluated angiography results based on the operator (either interventional radiologist or trauma surgeon) of the initial angiographic procedure. Re-embolization due to rebleeding was defined as embolization performed during a second angiography because of significant extravasation observed on angiography. Surgery due to rebleeding was defined by procedures such as laparotomy or preperitoneal pelvic packing undertaken due to bleeding indicators, such as hypotension or decreased serum hemoglobin, even after the first angioembolization. Each patient who experienced rebleeding underwent a transfusion of a minimum of 2 U of red blood cells. The term “failure of the first angioembolization,” which referred to overall rebleeding, encompassed both re-embolization and surgery due to rebleeding. The primary outcome of our study was the failure rate of the first angioembolization, and the secondary outcome was in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical data are presented as proportions and were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using R ver. 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). We constructed a multivariable logistic regression (MLR) model to analyze failure of the first angioembolization. Variables with a P-value of <0.2 from the univariable analysis were incorporated into the MLR model. The operator’s effect on angiography was also considered in the MLR model. We used the backward elimination method for fitting the MLR model.

RESULTS

The comparison of angiographic procedures performed by dedicated interventional radiologists versus those performed by a trauma surgeon is summarized in Table 1. Factors such as age, vital signs, GCS score, ISS, and AIS score for each body region were not significantly different between the groups. The trauma surgeon was more inclined to perform pelvic embolization and use Gelfoam as an embolic agent. There were no significant differences between the radiologic interventionists and the trauma surgeon in terms of re-embolization due to rebleeding, surgery due to rebleeding, or the overall failure rate of the first angioembolization. Likewise, mortality and morbidity rates were comparable between the two groups.

Comparison between angiography procedures performed by dedicated interventional radiologists and a single trauma surgeon

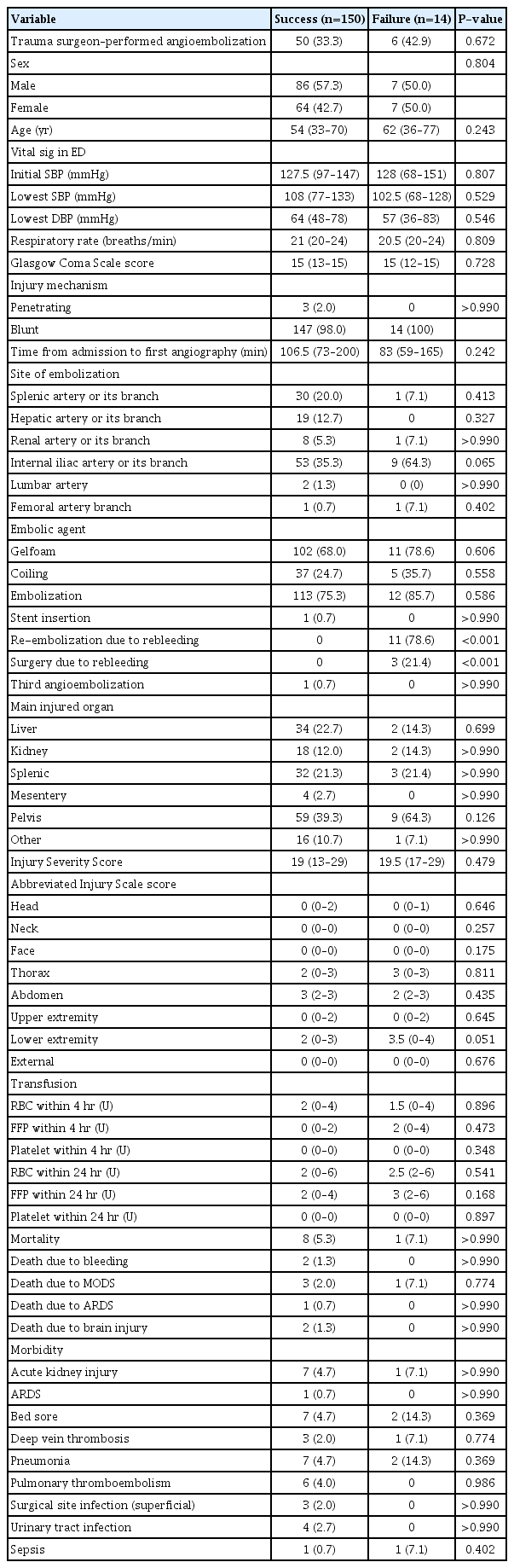

A comparison between patients who exhibited no rebleeding (termed “success”) and those who did experience rebleeding (termed “failure”) after the initial embolization is presented in Table 2. No significant difference was found related to the operator or angiographic procedure (P=0.672). Pelvic embolization, targeting the internal iliac artery or its branches, occurred more frequently in the failure group (35.3% vs. 64.3%), but this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.065). The median AIS score for the lower extremities was higher in the failure group, though without reaching statistical significance (2 [IQR, 0–3] vs. 3.5 [IQR, 0–4]; P=0.051).

Comparison between patients with outcomes of success (no rebleeding) and failure (rebleeding) after initial embolization (n=164)

Table 3 presents the MLR model assessing the risk of failure following the initial embolization. Pelvic embolization emerged as the only significant risk factor in the MLR analysis (adjusted odds ratio, 3.29; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–10.33; P=0.041). The clinical specialty of the angioembolization operator (i.e., interventional radiologist or trauma surgeon) was not a significant risk factor in the MLR model.

DISCUSSION

Emergency angioembolization can be safely and effectively performed by trauma surgeons. In this study, the rates of rebleeding and mortality after trauma surgeon–performed angioembolization were comparable to those seen with angioembolization carried out by interventional radiologists. The procedure was effective in treating significant hemorrhages in the liver, spleen, kidney, and pelvis. The low rebleeding rate (10.7%) and mortality rate (5.4%) post-angioembolization by the trauma surgeon in our study seem acceptable. These findings suggest that trauma surgeons, when equipped with the appropriate training and experience, can deliver emergency angioembolization results similar to those of specialized interventional radiologists. Equipping trauma surgeons with endovascular skills could improve the promptness and effectiveness of trauma care, especially at centers where interventional radiologists are not consistently available. Continuous training and collaboration between trauma surgeons and interventional radiologists can optimize patient care and outcomes. We see potential for a paradigm shift toward rapid, specialized hemostasis for unstable traumatic injuries.

Angioembolization for noncompressible torso hemorrhage has become essential in modern trauma care [8–11]. Angioembolization is also crucial for pelvic fractures with severe hemorrhage. A recent retrospective study [13] using the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) database showed that pelvic angiography reduced mortality independently. In contrast, the study found no mortality reduction associated with pelvic packing or zone 3 resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. Rapid nonselective pelvic angioembolization appears beneficial for unstable patients [14]. For critical abdominal solid organ injuries like those affecting the liver, spleen, or kidneys, angioembolization is recommended as a less invasive and effective hemostatic alternative for patients stable enough to undergo surgery [9–11]. Various guidelines recommend nonoperative management, including angioembolization, for hemodynamically stable patients [9–11]. Thus, angioembolization has become indispensable at modern trauma centers. However, ensuring a sufficient number of interventional radiologists is challenging in Korea. Providing 24/7 coverage year-round intensifies the workload and increases fatigue among the personnel of trauma centers. Given trauma surgeons’ constant presence, they may be viable alternatives, as they have extensive familiarity and involvement in all treatment phases.

The concept of surgeons performing endovascular procedures is not new. In recent decades, vascular surgeons have integrated endovascular techniques into their practices for various vascular diseases [15–17]. Nevertheless, globally, reports about trauma surgeons conducting endovascular procedures are scarce [6,18,19]. Herrold et al. [19], in their report of a retrospective study from R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center in the United States, proposed a 6-month acute care surgeon fellowship that would include training in arterial access, diagnostic angiography, embolization, stent placement, and inferior vena cava filter procedures. The authors emphasized the need to establish an endovascular trauma curriculum. Tsurukiri et al. [20], from Tokyo Medical University Hachioji Medical Center in Japan, described acute vascular interventional radiology techniques, both trauma-related and non–trauma-related, performed by acute care specialists trained for over 1 year as part of the endovascular team in their radiology department. They noted the acute care specialist’s ability to respond immediately to emergencies, contrasting with the often-limited availability of in-house radiologists outside regular hours. These specialists were not trauma surgeons but acute care physicians, as trauma surgeons were not consistently present. The specialists were considered alternatives. Upon reviewing previous literature, we found no further reports from other institutions in other countries.

In our study, 90 of 164 patients (54.8%) underwent angioembolization during off-hours (from 6 PM to 8 AM the following day). Starting in June 2022, our center had only one available interventional radiologist. Consequently, securing this radiologist’s services during off-hours proved challenging. To address this issue, a trauma surgeon with vascular subspecialty training began performing emergency angioembolization procedures. Matsumoto et al. [21] introduced concepts such as damage control interventional radiology (DCIR) and prompt and rapid endovascular strategies in traumatic situations (PRESTO). A trauma surgeon would be able to perform this role well. Generally, interventional radiologists might not have extensive experience or training in the initial resuscitation or assessment of severe traumatic injuries. A holistic understanding of the entire treatment process, including subsequent surgical procedures, such as laparotomy or pelvic packing, is vital for determining the optimal embolization site (whether proximal or selective) and method (using Gelfoam or coiling).

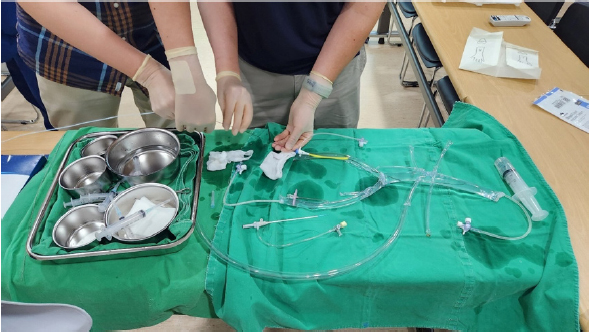

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first presenting outcomes for a trauma surgeon performing emergency angioembolization for trauma patients in Korea. Even at our nation’s level I trauma centers, all angioembolization-related procedures have traditionally been the domain of interventional radiologists. In contrast, at our facility, this role has been assumed by a single trauma surgeon. This was made possible by his prior experience with interventional radiology for vascular ailments. To enable other trauma surgeons to perform angioembolization, we developed a dry lab simulator that mimics the aorta and its branches, including the celiac trunk, splenic artery, renal artery, and internal iliac artery (Fig. 1). All attending trauma surgeons at our center were trained in both the theoretical and practical aspects of interventional radiology. This involved practicing vascular selection using a guidewire paired with an endovascular catheter and mastering coil insertion techniques. Our goal is to equip every attending trauma surgeon at our center with these endovascular competencies. We hope that our initiative will lay the foundation for the establishment of an endovascular certification specifically for trauma surgeons. In the United States, there have been several trials regarding endovascular training for trauma surgeons, but it has not yet become widespread or standardized [6,18].

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, its retrospective design might have introduced considerable bias. To more conclusively ascertain the safety and efficacy of angioembolization performed by trauma surgeons, further prospective research is recommended. Second, angioembolization was conducted by a single trauma surgeon who had experience with endovascular procedures for vascular diseases. Other trauma surgeons have not yet received adequate training for such endovascular procedures. Nonetheless, we intend to train all trauma surgeons to develop this endovascular skill set. Third, while not statistically significant, the rebleeding rate was higher in embolization of the internal iliac artery or its branches than at other sites. However, additionally, the failure rate of angioembolization did not differ notably between interventional radiologists (5 of 27, 15.6%) and the trauma surgeon (4 of 26, 13.3%; P>0.99). Further research is needed regarding this issue. Finally, we did not include other endovascular procedures, such as peripherally inserted central catheters, central venous catheterization, percutaneous catheter drainage of hemothorax, or inferior vena cava filter insertions. At our hospital, trauma surgeons also perform these procedures in a specialized angiographic suite. In future research, we plan to investigate these procedures.

Conclusions

A trauma surgeon with the necessary endovascular skills and experience can safely perform angioembolization. Their expertise and understanding of damage control resuscitation may improve the outcomes of angioembolization procedures. Even when an in-house interventional radiologist is absent during off-hours, a trauma surgeon with these endovascular skills could be available. Nevertheless, a refined training curriculum is essential for trauma surgeons to ensure quality control.

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SK, WSK; Data curation: all authors; Formal analysis: SK, WSK; Methodology: SK, WSK; Project administration: WSK; Supervision: WSK; Visualization: WSK; Writing–original draft: SK, WSK; Writing–review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Wu Seong Kang is an Editorial Board member of the Journal of Trauma and Injury, but was not involved in in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this study.

Data availability

Data analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.