Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Trauma Inj > Volume 36(4); 2023 > Article

-

Original Article

Perceptions regarding the multidisciplinary treatment of patients with severe trauma in Korea: a survey of trauma specialists -

Shin Ae Lee, MD1,2

, Yeon Jin Joo, RN1,3

, Yeon Jin Joo, RN1,3 , Ye Rim Chang, MD1,2

, Ye Rim Chang, MD1,2

-

Journal of Trauma and Injury 2023;36(4):322-328.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20408/jti.2023.0045

Published online: December 1, 2023

- 617 Views

- 32 Download

1Department of Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2Trauma Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

3Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- Correspondence to Ye Rim Chang, MD Department of Surgery, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 101 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea Tel: +82-2-2072-0937 Email: yerimchang@gmail.com

Copyright © 2023 The Korean Society of Traumatology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

Purpose

- Patients with multiple trauma necessitate assistance from a wide range of departments and professions for their successful reintegration into society. Historically, the primary focus of trauma treatment in Korea has been on reducing mortality rates. This study was conducted with the objective of evaluating the current state of multidisciplinary treatment for patients with severe trauma in Korea. Based on the insights of trauma specialists (i.e., medical professionals), we aim to suggest potential improvements.

-

Methods

- An online questionnaire was conducted among 871 surgical specialists who were members of the Korean Society of Traumatology. The questionnaire covered participant demographics, current multidisciplinary practices, perceived challenges in collaboration with rehabilitation, psychiatry, and anesthesiology departments, and the perceived necessity for multidisciplinary treatment.

-

Results

- Out of the 41 hospitals with which participants were affiliated, only nine conducted multidisciplinary meetings or rounds with nonsurgical departments. The process of transferring patients to rehabilitation facilities was not widespread, and delays in these transfers were frequently observed. Financial constraints were identified by the respondents as a significant barrier to multidisciplinary collaboration. Despite these hurdles, the majority of respondents acknowledged the importance of multidisciplinary treatment, especially in relation to rehabilitation, psychiatry, and anesthesiology involvement.

-

Conclusions

- This survey showed that medical staff specializing in trauma care perceive several issues stemming from the absence of a multidisciplinary system for patient-centered care in Korea. There is a need to develop an effective multidisciplinary treatment system to facilitate the recovery of trauma patients.

- Background

- A survey carried out by the Ministry of Health and Welfare demonstrated a significant decrease in the national average preventable trauma mortality rate, from 30.5% in 2015 to 15.7% in 2019 [1]. The establishment of regional trauma centers in Korea has improved trauma treatment, and the nationwide preventable trauma mortality rate has declined.

- To date, trauma treatment in Korea has primarily focused on reducing mortality rates. The indicators used to evaluate regional trauma centers and the parameters of the Korean Trauma Database (KTDB) are limited to resuscitation, acute-phase outcomes, and mortality. Although a multidisciplinary system is implemented in Korea, it primarily comprises surgical departments.

- However, patients with multiple trauma necessitate the involvement of numerous departments and professions until they can be successfully reintegrated into society. As such, trauma care must span all stages of recovery, forming a continuous process. Ideally, enhancements in acute care quality should be seamlessly integrated with those in rehabilitation and recovery. A multidisciplinary approach is of the utmost importance in facilitating survivors’ functional recovery, improving their quality of life, and reintegrating into society.

- Objectives

- As a preliminary step toward establishing a foundation for multidisciplinary treatment in trauma care, this study aimed to investigate the current state and problems regarding multidisciplinary treatment for patients with severe trauma in Korea, obtain insights into ways of improving the system by conducting a perception survey among trauma specialists (medical professional), and generate more interest in this subject.

INTRODUCTION

- Ethics statement

- This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (No. 2112-129-1284). Written informed consent was obtained from the respondents. An online questionnaire-based survey was conducted following the CHERRIES (Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys) statement [2].

- Study design

- In total, 871 surgical specialists from 1,500 members of the Korean Society of Traumatology were selected as the target population. The questionnaire was created using Google Forms (Google) and sent via email. Only those who indicated their willingness to participate were included in the study. The survey was launched at the end of November 2021, and remained open until December 2021.

- The questionnaire consisted of 43 items, which could be categorized into the following: (1) the characteristics of the survey participants (major subject, hospital size, and location); (2) the current status of multidisciplinary meetings and rounds; (3) perceptions of problems with the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine; (4) perceptions of problems with the Department of Psychiatry; (5) perceptions of problems with the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine; (6) perceptions of medical staff on the need for multidisciplinary treatment; (7) status of medical care after discharge; and (8) comments. A combined total, with each section consisting of a minimum of 4 to a maximum of 16, was considered (Table S1). Categories 3 through 7 only included answers from staff of regional trauma centers and final treatment centers. Final treatment centers are designated by the Seoul Metropolitan Government (Seoul, Korea), and a total of four final treatment centers are responsible for treating severe trauma patients in the Seoul area.

METHODS

- Characteristics of the survey participants

- Among the 41 hospitals with which participants were affiliated, there were 16 regional trauma centers (39.0%, only Mokpo Hankook Hospital [Mokpo, Korea] was not included), three final treatment centers in Seoul (7.3%), 15 certified tertiary hospitals (36.6%), and seven other hospitals (17.1%). Medical staff working at regional trauma and final treatment centers in Seoul accounted for 68.1% of the sample. Specialists in surgery (or trauma surgery), neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, and cardiothoracic surgery participated in the study in decreasing order.

- Among the survey respondents, a duration of work experience in the trauma field of more than 5 years was the most common (71.6%), followed by 2 to 5 years (16.4%) and ˂2 years (12.1%). Most participants worked in Seoul, followed by southern Gyeonggi Province, Daegu, northern Gyeonggi Province, Gangwon Province, and North Jeolla Province (Table S2).

- Multidisciplinary meetings and rounds

- Multidisciplinary meetings consisting of only surgical departments were excluded from the questionnaire analysis. Among the 41 hospitals with which participants were affiliated, only nine trauma centers had a multidisciplinary system (Table 1). Among the regional trauma and final treatment centers, only four held regular multidisciplinary meetings with the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine or the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Only Seoul National University Hospital, one of the final treatment centers in Seoul, held multidisciplinary meetings with the Departments of Rehabilitation Medicine, Psychiatry, Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, and Family Medicine. Only one regional trauma center conducted periodic multidisciplinary rounds among all hospitals. However, it should be kept in mind that, given the study design, it was not possible to gather information pertaining to hospitals other than those with which the study participants were affiliated.

- Status and issues of multidisciplinary treatment for trauma patients

- The analysis of the status and problems of multidisciplinary treatment for trauma patients only included responses from the medical staff of regional trauma centers and the final treatment centers in charge of treating severely injured patients. Respondents from only six hospitals answered that they could transfer patients to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine within the hospital if specialized rehabilitation was deemed necessary. In-hospital transfers to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine also seemed possible in the other two hospitals. However, respondents' answers were inconsistent within a single hospital, leading to the inference that such transfers may not always be feasible (Table 2).

- The most common response (40.5%) for the average time required for in-hospital transfer to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine or for transfer to a rehabilitation hospital was 1 to 2 week (Table 3).

- Furthermore, 57.0%, 31.7%, and 45.5% of responses indicated that there were always, frequently, or fairly often problems, respectively, due to the lack of support from the Departments of Rehabilitation Medicine, Psychiatry, and Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine (Table 4).

- Perceptions of the possible causes of lack of multidisciplinary support

- Based on the multiple responses received regarding the causes of lack of support from the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, respondents perceived the causes as shortage of staff in rehabilitation medicine (21.3%), a lack of network or protocol for multidisciplinary treatment for trauma patients (17.0%), a lack of specialized (certified) rehabilitation hospitals nearby that can accept transfers (16.5%), a shortage of beds at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine (13.9%), a lack of or excessively cheap insurance fees or reimbursements (13.5%), a lack of interest or enthusiasm the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine for trauma patients (9.6%), and a lack of information on rehabilitation hospitals that can accept transfers (7.8%) (Table 5).

- Regarding the lack of psychiatric support, a lack of a network or protocol for multidisciplinary treatment for trauma patients (20.6%) was the most common answer, followed by a shortage of hospitals that could accept transfers of patients with psychiatric problems (16.1%), a shortage of staff in the Department of Psychiatry (14.6%), and a lack of interest or enthusiasm in the Department of Psychiatry for trauma patients (14.1%) (Table 6).

- Perceptions of the need for multidisciplinary treatment

- Based on the responses on the need for multidisciplinary treatment in collaboration with the Departments of Rehabilitation Medicine, Psychiatry, and Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, 89.8%, 74.7%, and 56.9% of respondents who were medical staff of regional trauma centers and final treatment centers, respectively, answered that it was “very much needed” or “needed.” Including the answer “fairly needed,” the percentages increased to 97.4%, 93.7%, and 89.8%, respectively, which indicates that most of the medical staff treating patients with severe trauma had positive views on the necessity of multidisciplinary treatment (Table 7). Regarding the need for multifaceted evaluations of patients who have completed acute trauma treatment, 98.7% responded “very needed,” “needed,” or “fairly needed.”

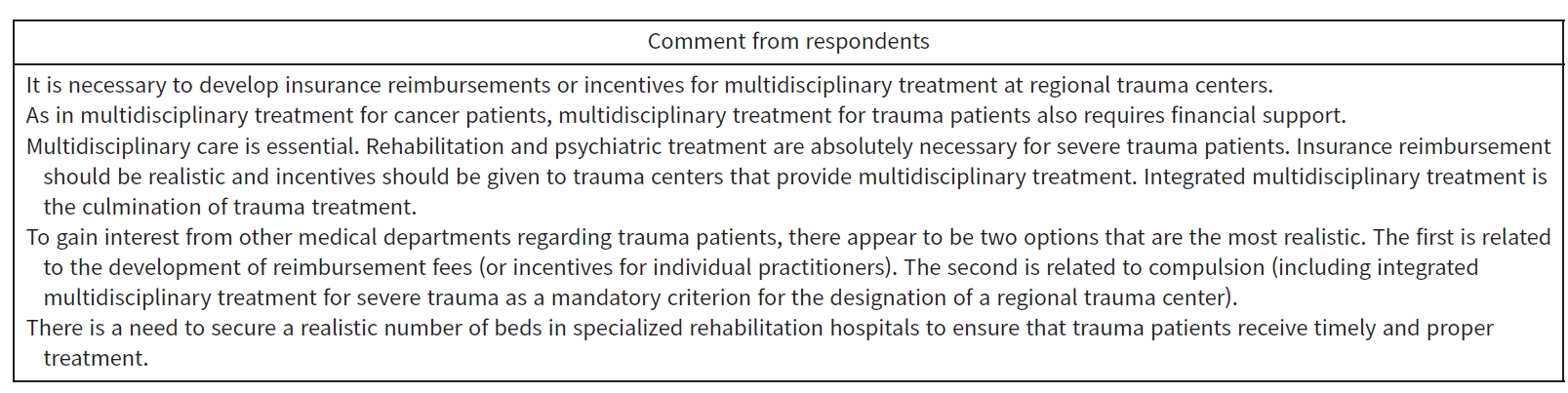

- Comments and suggestions from the respondents

- Most respondents pointed to financial issues in their comments and suggestions. Respondents suggested that there must be financial support, such as insurance reimbursement and incentives, for the multidisciplinary treatment of patients with trauma. One respondent suggested that the provision of multidisciplinary treatment for severe trauma should be a mandatory criterion for the designation of a regional trauma center (Fig. 1).

RESULTS

- The treatment of patients with multiple traumas cannot be confined solely to the surgical field. Moreover, trauma care should encompass a continuum that spans from resuscitation to postdischarge management. According to the Victorian State Trauma Registry [3], disability remains common 24 months after a traumatic injury, and 30% of patients could not return to work. Posttraumatic stress disorder (45%), psychiatric disorders (31%), alcoholism (26%), moderate-to-severe chronic pain (23%), and depression (18%) were commonly observed 1 year after injury [4,5]. Poor health-related quality of life, such as pain or physical discomfort (72%) and difficulties in self-care (31%) were also commonly observed [4].

- There is evidence that multidisciplinary treatment improves outcomes in patients with trauma, especially in the older adult population. Multidisciplinary teams described in the literature include nurses, rehabilitation therapists, respiratory therapists, nutritionists, and palliative care staff, in addition to specialists such as trauma surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and internists [6–9]. There is research reporting that shorter hospital stays and faster transfers to specialized trauma rehabilitation units, along with early initiation of multidisciplinary treatments and “nonweight bearing” mobilization, were achieved through integrated coordination between trauma surgeons and rehabilitation physicians, providing a “fast track” rehabilitation service for patients with an Injury Severity Score (ISS) >15 [10]. In another study [11], early physical medicine and rehabilitation consultation within 8 days of admission demonstrated a shorter length of stay in acute care, fewer complications, and reduced use of benzodiazepines and antipsychotics.

- In this study, trauma specialists in Korea perceived a lack of multidisciplinary support and collaboration in trauma care. Only nine trauma centers had a multidisciplinary system with nonsurgical departments. The respondents highlighted financial issues as one of the most significant potential causes of the lack of multidisciplinary support. A systematic review of multidisciplinary rehabilitation in patients with multiple traumas listed the reasons for the limited access to optimal rehabilitation programs, including a lack of political commitment to reform, inadequate financial support for infrastructure, and fragmented healthcare systems [12–14].

- Multidisciplinary treatment may become widely established with reasonable fees and national support. For example, in the United Kingdom, a best practice tariff is applied based on data collected by the Trauma Audit and Research Network (TARN), wherein incentives are paid to trauma care institutions whose performance is rated as excellent, and its calculation is reflective of the severity of trauma in patients treated by each center [15].

- The indicators used to evaluate regional trauma centers in Korea are limited to the initial stages of trauma treatment. The United Kingdom emphasizes the importance of rehabilitation for the recovery of trauma patients; hence, the process of identifying patients' rehabilitation needs and timely rehabilitation are included in the performance evaluation [15]. UK standards dictate that all patients with an ISS ≥9 should receive a standardized rehabilitation prescription. Rehabilitation needs must be assessed within 10 days of referral, and patients should be transferred to specialist rehabilitation within 6 weeks of being fit for transfer. Measurements of functional improvement and discharge destination were also recorded for quality control purposes [15]. In Australia and New Zealand, quality indicators include the time taken for rehabilitation from referral and the patient's discharge destination [16].

- Currently, quantitative data regarding recovery, long-term outcomes, and reintegration into society of trauma patients in Korea are lacking. The Victorian State Trauma Registry collects information on patient-reported health-related quality of life, time required to return to work, residential status, and healthcare utilization 6, 12, and 24 months after discharge [3]. This type of postdischarge patient-centered data is invaluable for identifying patients who recover, when they recover, and to what extent. It enables quantification of the burden of major trauma, which in turn aids in the planning of medical services [17].

- Limitations

- This study had certain limitations owing to the exclusion of certain medical staff from regional trauma centers, potentially resulting in missing information. Furthermore, as this survey primarily dealt with perceptions, it presents subjective information. Nonetheless, this study holds significance in confirming the necessity of a multidisciplinary system and offers important suggestions for subsequent phases of developing trauma treatment in Korea.

- Conclusions

- Drawing from this survey and the existing literature, the following suggestions can be put forth to enhance the quality of trauma treatment in Korea. Financial support should be provided through measures such as insurance reimbursement and incentives for multidisciplinary treatment involving various medical and surgical departments, rehabilitation-related indicators should be included in the quality assessment of regional trauma centers, and parameters for recovery and long-term outcomes should be incorporated into the KTDB.

DISCUSSION

-

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

This study was supported by the National Traffic Injury Rehabilitation Research Fund (No. NTRH RF-2021001) and Research Program of Korean Association for Research, Procedures on Education on Trauma (No. KARPET-21).

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: YRC; Data curation: SAL, YRC; Formal analysis: YJJ, YRC; Funding acquisition: YRC; Investigation: YJJ; Methodology: SAL, YRC; Project administration: SAL, YRC; Visualization: YJJ; Writing–original draft: SAL, YRC; Writing–review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chan Yong Park (Department of Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea) for the helpful comments on the questionnaire items.

-

Data availability

Data analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

| Response | No. of responses (%) |

|---|---|

| 1–2 day | 0 |

| 3–7 day | 31 (39.2) |

| 1–2 wk | 32 (40.5) |

| >2 wk | 6 (7.6) |

| Poorly transferred | 3 (3.8) |

| Highly variable | 7 (8.9) |

- 1. Kwon J, Lee M, Moon J, et al. National follow-up survey of preventable trauma death rate in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2022;37:e349ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 2. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e34ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Gabbe BJ, Sutherland AM, Hart MJ, Cameron PA. Population-based capture of long-term functional and quality of life outcomes after major trauma: the experiences of the Victorian State Trauma Registry. J Trauma 2010;69:532–6. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Bryant RA, O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, McFarlane AC, Clark CR, Silove D. The psychiatric sequelae of traumatic injury. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:312–20. ArticlePubMed

- 5. Spijker EE, Jones K, Duijff JW, Smith A, Christey GR. Psychiatric comorbidities in adult survivors of major trauma: findings from the Midland Trauma Registry. J Prim Health Care 2018;10:292–302. ArticlePubMed

- 6. DeLa’O CM, Kashuk J, Rodriguez A, Zipf J, Dumire RD. The Geriatric Trauma Institute: reducing the increasing burden of senior trauma care. Am J Surg 2014;208:988–94. ArticlePubMed

- 7. Henderson CY, Shanahan E, Butler A, et al. Dedicated orthogeriatric service reduces hip fracture mortality. Ir J Med Sci 2017;186:179–84. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 8. Mangram AJ, Shifflette VK, Mitchell CD, et al. The creation of a geriatric trauma unit “G-60”. Am Surg 2011;77:1144–6. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Wallace R, Angus LD, Munnangi S, Shukry S, DiGiacomo JC, Ruotolo C. Improved outcomes following implementation of a multidisciplinary care pathway for elderly hip fractures. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019;31:273–8. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 10. Bouman AI, Hemmen B, Evers SM, et al. Effects of an Integrated ‘fast track’ rehabilitation service for multi-trauma patients: a non-randomized clinical trial in the Netherlands. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170047ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Robinson LR, Tam AK, MacDonald SL, et al. The impact of introducing a physical medicine and rehabilitation trauma consultation service to an academic level 1 trauma center. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2019;98:20–5. ArticlePubMed

- 12. Wilson T, Holt T, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: complexity and clinical care. BMJ 2001;323:685–8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Hoyt DB, Coimbra R. Trauma systems. Surg Clin North Am 2007;87:21–35. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Khan F, Amatya B, Hoffman K. Systematic review of multidisciplinary rehabilitation in patients with multiple trauma. Br J Surg 2012;99 Suppl 1:88–96. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. McCullough AL, Haycock JC, Forward DP, Moran CG. II. Major trauma networks in England. Br J Anaesth 2014;113:202–6. PubMed

- 16. Kovoor JG, Jacobsen JH, Balogh ZJ, Trauma Care Verification and Quality Improvement Writing Group. Quality improvement strategies in trauma care: review and proposal of 31 novel quality indicators. Med J Aust 2022;217:331–5. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Rios-Diaz AJ, Lam J, Zogg CK. The need for postdischarge, patient-centered data in trauma. JAMA Surg 2016;151:1101–2. ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

KST

KST

PubReader

PubReader Cite

Cite